How Cloud ERP Works: The Technical Architecture Behind Modern Business Systems

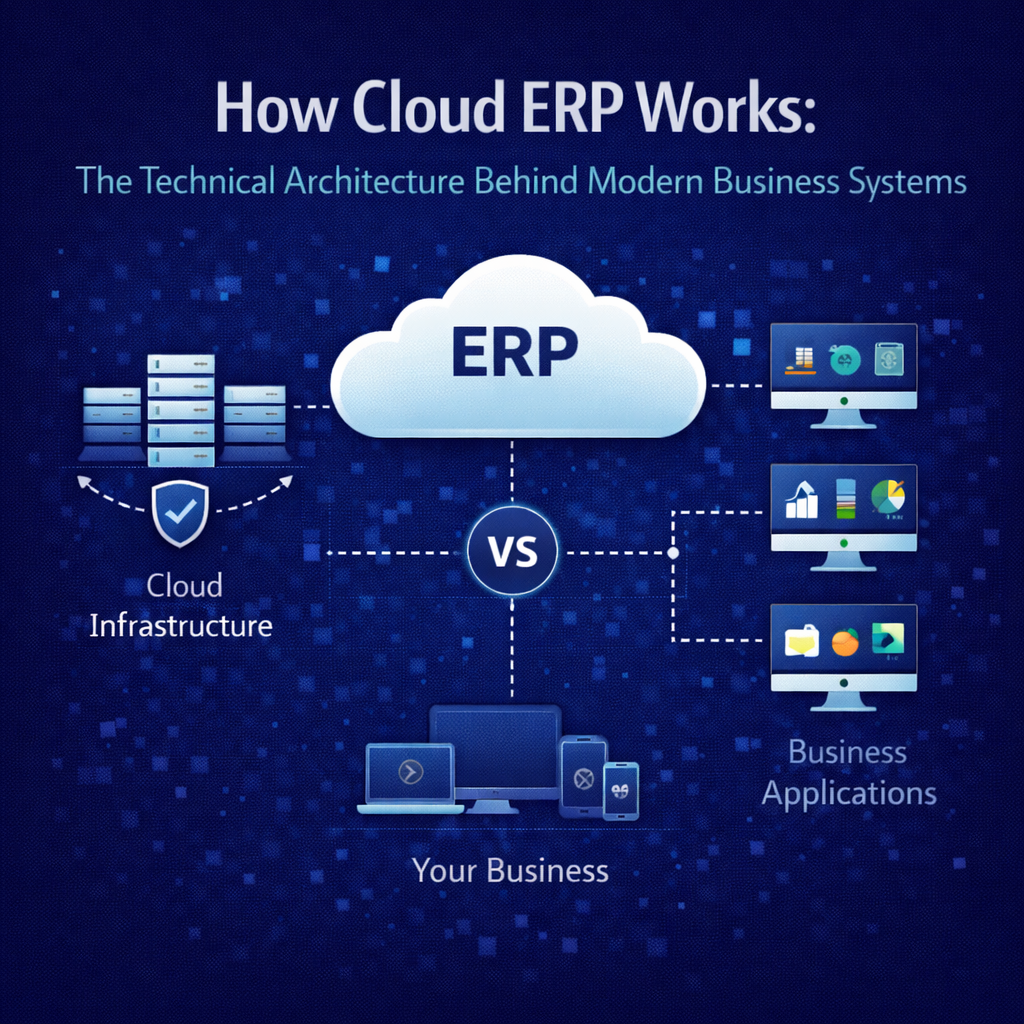

Most cloud ERP content talks about what the software does. Very little explains how it actually works — the architecture underneath, the design decisions that determine performance and reliability, and the technical foundations that separate platforms built for the cloud from platforms relocated to it.

This gap isn’t accidental. Vendors that migrated legacy on-premise systems to hosted environments have every incentive to keep the architectural conversation superficial. If buyers understood what was actually running behind the login screen — how data flows, how updates deploy, how the system scales, how transactions process — the gap between cloud-native and cloud-washed would be impossible to obscure.

This guide is for the people making ERP decisions who want to understand the machinery, not just the marketing. You don’t need to be a software engineer to follow it. But by the end, you’ll understand enough about cloud ERP architecture to evaluate vendors with sharper questions and to recognize when technical claims don’t match technical reality.

The Foundation: Where Cloud ERP Actually Runs

Cloud ERP platforms run on infrastructure provided by hyperscale cloud providers — primarily Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform. These providers operate massive global networks of data centers that deliver compute power, storage, networking, and a wide array of managed services that application developers can build on.

When you access a cloud ERP system through your browser, your request travels over the internet to one of these data centers, where the application processes it and returns the result. The physical servers, the networking equipment, the power systems, the cooling, the physical security — all of it is managed by the cloud infrastructure provider. The ERP vendor builds and operates the application layer on top of this foundation.

This separation matters because it means the ERP vendor doesn’t need to build and maintain their own data centers. They leverage infrastructure that represents billions of dollars in investment by AWS, Azure, or Google — investment in redundancy, security, performance, and global reach that no ERP vendor could replicate independently. The vendor focuses on what they should be best at: building and operating the application that runs your business. The infrastructure provider focuses on what they’re best at: running reliable, secure, scalable computing infrastructure.

For distribution companies, the practical implication is that your ERP runs on the same caliber of infrastructure that powers Netflix, Airbnb, and the largest technology companies in the world. The reliability, the geographic redundancy, the security investment, and the scalability of that infrastructure are available to a 50-person distribution company for the same per-unit cost as a Fortune 500 enterprise. That’s a structural economic advantage that didn’t exist when ERP systems ran on servers in your building.

The Application Layer: Where Architecture Diverges

The infrastructure layer is largely standardized — most cloud ERP vendors run on one of the three major providers. The architectural differences that actually affect your experience live in the application layer: how the ERP software itself is designed, how it manages data, how it processes transactions, and how it delivers updates.

This is where the distinction between cloud-native and cloud-migrated becomes technical rather than theoretical.

Cloud-Native Architecture

A cloud-native ERP platform was designed from its inception to run as a distributed, internet-delivered application. Its architecture assumes cloud infrastructure as the deployment target, which influences every design decision from the database layer through the user interface.

Cloud-native applications are typically built using modern software engineering patterns. The application may be composed of loosely coupled services that communicate through well-defined interfaces, allowing individual components to be updated, scaled, or replaced without affecting the rest of the system. The database layer is designed for concurrent access by many users across many organizations. The user interface is built for the browser as a primary delivery mechanism, not as an afterthought bolted onto a desktop-first design.

Because the application was designed for the cloud, it takes full advantage of cloud infrastructure capabilities. Compute resources scale dynamically based on demand. Storage expands automatically. Load balancing distributes traffic across multiple servers to prevent any single point of failure from affecting availability. The application is aware that it runs in a distributed environment and is designed to handle the realities of that environment — network latency, eventual consistency where appropriate, graceful degradation under load.

Cloud-Migrated Architecture

A cloud-migrated ERP platform was originally designed to run on a dedicated server in a single location. It was later moved to cloud infrastructure — sometimes with significant re-engineering, sometimes with minimal changes beyond swapping the physical server for a virtual one.

The telltale signs of migrated architecture are visible in how the system behaves. The application may still be fundamentally monolithic — a single large codebase that must be deployed as a unit, making updates larger and riskier. The database layer may still assume single-server deployment, creating performance bottlenecks when multiple customers or high-volume operations compete for database resources. The user interface may be a web layer built on top of a desktop application framework, resulting in an experience that feels like remote access to a desktop program rather than a native web application.

Migrated applications can function adequately on cloud infrastructure, but they don’t leverage it fully. They can’t scale elastically because the application wasn’t designed for dynamic resource allocation. They can’t deliver continuous updates easily because the monolithic architecture makes incremental deployment difficult. They carry the performance characteristics and limitations of their original design, regardless of how modern the infrastructure underneath them might be.

The difference isn’t always visible in a demo. Both architectures can produce clean, functional interfaces. The difference emerges under operational conditions — during peak transaction volumes, during concurrent multi-user activity, during data-intensive reporting, and over time as the vendor tries to evolve the platform while maintaining compatibility with its legacy foundations.

The Data Layer: Why Architecture Determines Everything

If there’s a single architectural decision that determines how a cloud ERP platform performs in daily operation, it’s how the data layer is designed. Everything else — the features, the interface, the integration capabilities — is constrained or enabled by the data architecture underneath.

Unified Data Architecture

In a unified data architecture, every function in the system — financial accounting, inventory management, purchasing, sales order processing, warehouse operations, shipping, customer management — reads from and writes to a single, shared database. There are no separate databases for separate modules. There are no batch synchronization processes moving data between functional areas. A single transaction creates a single record that is immediately visible and consistent across the entire system.

When a warehouse associate scans a receiving barcode, the inventory count updates, the purchase order status changes, the financial accrual posts, and the available-to-promise calculation adjusts — all from that single scan event, all in the same transactional moment. The sales team sees updated availability instantly. Purchasing sees the receipt against the open PO. Finance sees the liability. No reconciliation required because there’s nothing to reconcile — every view is reading the same data.

This architecture is what makes genuine real-time visibility possible. It’s not a reporting feature or a dashboard option. It’s a structural characteristic of how the system stores and retrieves information. Platforms that claim real-time visibility but run on separate databases per module are assembling a composite view from multiple sources — which introduces latency, creates reconciliation overhead, and occasionally produces inconsistencies when the sources disagree.

Modular Data Architecture

Legacy ERP systems — including many that now run on cloud infrastructure — were built with separate databases or schemas for each functional module. The finance module has its database. The inventory module has its database. The purchasing module has its database. Data moves between them through integration processes — sometimes in real time through middleware, more commonly in batches that run on a schedule.

This architecture was a practical necessity in the era when these systems were designed. Database technology, memory, and processing power were expensive, and separating concerns into distinct data stores was a reasonable engineering trade-off. But it creates permanent limitations that cloud infrastructure can’t fix.

Batch-processed data introduces latency. If inventory transactions sync to the financial system every four hours, the financial picture is always up to four hours behind operational reality. If sales order data syncs to the warehouse system on a schedule, the warehouse may be working from allocation data that doesn’t reflect the most recent orders.

Modular data creates reconciliation overhead. When the inventory module says you have 1,000 units and the financial module’s valuation is based on 985 units because the last sync hasn’t run yet, someone has to figure out which number is right. Multiply this across hundreds of SKUs, multiple locations, and every functional boundary in the system, and reconciliation becomes a permanent, labor-intensive process.

And modular data complicates reporting. Any report that spans functional areas — inventory valuation, order profitability, supplier performance with financial impact — has to pull from multiple databases and reconcile the results. The report is only as current as the oldest data source it draws from, and the reconciliation logic itself becomes a potential source of error.

Multi-Tenant vs. Single-Tenant: The Deployment Decision

How the application serves multiple customers is one of the most consequential architectural decisions in cloud ERP, and it affects everything from update frequency to cost economics.

Multi-Tenant Architecture

In a multi-tenant architecture, all customers share a single instance of the application running on shared infrastructure. Each customer’s data is logically isolated — encrypted, access-controlled, and completely invisible to other customers — but the application code, the database engine, and the compute infrastructure are shared.

This design enables several capabilities that single-tenant architectures struggle to deliver.

Continuous updates become practical because the vendor maintains one codebase for all customers. When an improvement is deployed, it’s deployed once, to the shared platform, and every customer benefits immediately. There’s no matrix of customer-specific versions to maintain, no compatibility testing for individual instances, no scheduling of customer-by-customer deployments.

Cost efficiency improves because infrastructure resources are pooled. The compute capacity that serves one customer during their peak hours can serve another customer in a different time zone during their peak. Storage, networking, security monitoring, and platform management costs are amortized across the entire customer base rather than duplicated for each customer.

Operational reliability benefits from the shared model because the vendor has strong incentive and practical ability to invest in platform-level reliability. Redundancy, failover, monitoring, and incident response protect all customers simultaneously. The per-customer cost of this protection is a fraction of what it would cost to build equivalent reliability for each customer independently.

The logical data isolation in a well-architected multi-tenant system is absolute. Customer A cannot access Customer B’s data through any application pathway. The isolation is enforced at multiple layers — application logic, database permissions, encryption, and access controls. This is the same isolation model used by every major SaaS application you already rely on, from your email provider to your banking application.

Single-Tenant Architecture

In a single-tenant architecture, each customer runs their own dedicated instance of the application on their own infrastructure allocation. The application code may be the same across customers, but each customer’s instance operates independently.

Single-tenant architecture offers one genuine advantage: physical resource isolation. Your application instance doesn’t share compute or database resources with other customers, which eliminates any theoretical risk of one customer’s workload affecting another’s performance. For organizations with specific regulatory requirements mandating physical infrastructure separation, this may be a necessary constraint.

The trade-offs are significant. Updates must be deployed to each customer instance individually, which makes continuous deployment impractical at scale. The result is the same version-fragmentation problem that plagued on-premise software: customers delay updates, fall behind on versions, and eventually run software that’s months or years out of date. Infrastructure costs are higher because resources can’t be pooled — each customer pays for their own capacity, sized for their own peak load, regardless of average utilization. And the vendor’s operational burden increases proportionally with the customer count, which drives up costs that are ultimately passed to customers.

For most mid-market distribution companies, the single-tenant trade-offs — higher cost, slower updates, version fragmentation — outweigh the isolation benefit, which can be achieved through logical separation in a well-architected multi-tenant platform without the associated disadvantages.

How Transactions Process: The Mechanics of Daily Operation

Understanding how a cloud ERP system processes a transaction — from the moment a user initiates an action to the moment the result is committed and visible — illuminates why architecture matters to daily operations.

The Lifecycle of an Order

Consider a customer order arriving via EDI — one of the most common transactions in distribution.

The EDI document arrives at the platform’s integration layer, which parses the incoming data, validates it against expected formats and business rules, and translates it into the system’s internal data structure. If the document is malformed or contains invalid data, the system flags it for review rather than processing it blindly.

The validated order enters the order management workflow. The system checks the customer’s credit status against current receivables and credit limits. It applies the correct pricing — which may involve customer-specific pricing agreements, volume tiers, contract terms, or matrix calculations based on product attributes. It validates product codes against the item master. All of this happens programmatically, in fractions of a second.

Inventory allocation occurs next. The system checks real-time available inventory across all eligible locations, applies allocation rules — which warehouse to fulfill from, how to handle partial availability, whether to backorder or split-ship — and reserves the allocated units against the order. These reserved units are immediately reflected in the available-to-promise calculations visible to every other user and every other process in the system. If another order arrives a millisecond later requesting the same product, it sees the post-allocation inventory position, not the pre-allocation position. This is what real-time means at the transactional level.

The allocated order generates warehouse work — pick tasks directed to the appropriate locations within the fulfillment warehouse. In a system with advanced warehouse management, these tasks are optimized based on warehouse geography, picking methodology, and current workload. The warehouse associate receives the task on a mobile device, confirms each pick with a scan, and the system updates inventory positions as picks are completed.

Packing and shipping follow, with the system generating packing lists, calculating freight through integrated carrier connections, producing shipping labels, and capturing tracking information. Shipment confirmation triggers the final downstream events: the invoice generates automatically based on what was actually shipped, the financial entries post — revenue recognition, cost of goods sold, accounts receivable — and the order status updates to reflect completion.

This entire sequence, from EDI receipt to financial posting, can complete in minutes on a platform with unified data architecture and integrated workflows. On a system with modular data and disconnected processes, the same sequence involves manual handoffs, batch processing delays, and reconciliation steps that stretch it across hours or days.

Transaction Integrity

Every step in this sequence involves database operations that must be reliable. If the system crashes mid-transaction — after allocating inventory but before confirming the pick, for example — the data must remain consistent. Cloud ERP platforms handle this through transactional guarantees at the database level: either all of the operations within a transaction complete successfully, or none of them do. There’s no state where inventory is allocated but the order doesn’t reflect it, or where a shipment is confirmed but the invoice doesn’t generate.

This transactional integrity is fundamental to data reliability, and it’s one of the areas where unified data architecture provides a clear advantage. When all operations occur within a single database, transactional guarantees are straightforward to implement and enforce. When operations span multiple databases — as in modular architectures — maintaining transactional integrity across database boundaries requires distributed transaction protocols that are significantly more complex and more prone to edge-case failures.

How Updates Deploy: Continuous vs. Versioned

The update deployment model is an architectural characteristic, not a policy choice. How a platform delivers updates is determined by how it was built.

Continuous Deployment

Multi-tenant platforms deploy updates to the shared application instance in a process that’s typically invisible to users. The vendor’s engineering team develops and tests changes against the production environment, deploys them during maintenance windows or through blue-green deployment strategies that route traffic seamlessly between the old and new versions, and monitors for any issues post-deployment.

Because every customer runs on the same instance, every customer receives the update simultaneously. There’s no rollout schedule. There’s no customer-by-customer testing. The vendor tests against one environment — the production platform — and deploys once. New features, performance improvements, bug fixes, and security patches reach every customer as soon as they’re deployed.

This model allows for frequent, incremental updates rather than infrequent, large releases. Small changes deployed often are inherently lower risk than large changes deployed rarely. Each deployment is easier to test, easier to monitor, and easier to roll back if an issue is discovered. The result is a platform that improves continuously in small increments rather than in large, disruptive jumps.

Versioned Deployment

Single-tenant platforms and hosted legacy systems deploy updates as discrete versions. The vendor releases Version 12.3, and each customer must schedule, test, and execute the migration from their current version to the new one. This process typically involves a staging environment where the update is tested against the customer’s specific configuration, data, and integrations before being applied to production.

The overhead of this process discourages frequent updates. Vendors batch changes into larger, less frequent releases — quarterly, semiannually, or annually — to reduce the deployment burden. But larger releases carry more risk, require more testing, and create longer periods between improvements. Customers who find the upgrade process burdensome — which is most customers — delay even further, falling multiple versions behind.

The architectural root cause is that single-tenant instances can diverge in configuration, customization, and data structure over time. Each instance becomes slightly unique, and that uniqueness makes universal deployment impractical. Multi-tenant architecture avoids this by design: the shared platform enforces consistency, which makes continuous deployment not just possible but natural.

How Security Works at the Platform Level

Cloud ERP security operates across multiple layers, each addressing different categories of risk.

The infrastructure layer is secured by the cloud provider — physical access controls, network isolation, DDoS protection, and hardware-level encryption. The application layer is secured by the ERP vendor — authentication, authorization, role-based access controls, data encryption at rest and in transit, and application-level vulnerability management. The data layer is secured through isolation mechanisms — tenant-specific encryption keys, database-level access controls, and application logic that enforces data boundaries.

In a multi-tenant platform, security is a shared concern that the vendor addresses at the platform level. When a vulnerability is identified — in the application code, in a dependency, or in the underlying framework — the patch is deployed once and protects every customer immediately. There’s no window of exposure while individual customers schedule their own patching. There’s no version fragmentation creating a landscape where some customers are protected and others aren’t.

Authentication increasingly involves multi-factor mechanisms — something you know (password) combined with something you have (authenticator app or hardware token) — to protect against credential-based attacks. Role-based access controls ensure that users can only access the data and functions relevant to their role. A warehouse associate sees warehouse functions. A purchasing manager sees purchasing functions. A controller sees financial data. The system enforces these boundaries regardless of the access pathway.

Audit logging captures every significant system event — logins, data changes, configuration modifications, report access — creating a trail that supports compliance requirements, internal controls, and forensic investigation if needed. In a well-architected platform, these logs are immutable and accessible to authorized administrators without requiring vendor intervention.

How Integration Architecture Works

Distribution businesses connect their ERP to dozens of external systems — e-commerce platforms, EDI networks, shipping carriers, payment processors, banking systems, CRM tools, and specialized applications. How the ERP handles these connections determines the reliability, maintainability, and cost of your integration ecosystem.

API-First Design

Modern cloud ERP platforms expose their functionality through APIs — Application Programming Interfaces — that provide standardized, documented access to system data and operations. An API-first design means the same interfaces used by the platform’s own user interface are available to external systems, which ensures that integrations have access to the full depth of platform functionality.

RESTful APIs — the most common standard — use standard HTTP protocols and data formats that virtually every modern system can work with. Well-documented APIs include endpoint definitions, authentication requirements, data schemas, rate limits, and error handling conventions. They allow developers — your own team or your vendor’s — to build reliable integrations without requiring proprietary toolkits or specialized knowledge.

Webhooks and Event-Driven Integration

Beyond request-response APIs, modern platforms support event-driven integration through webhooks. Instead of an external system repeatedly checking the ERP for changes — “has anything happened yet? has anything happened yet?” — the ERP proactively notifies the external system when a relevant event occurs. An order ships: the ERP pushes a notification to the e-commerce platform. A payment is received: the ERP notifies the banking integration. An inventory threshold is crossed: the ERP alerts the purchasing system.

Event-driven integration is more efficient, more timely, and more reliable than polling-based approaches. It reduces unnecessary network traffic, ensures external systems react to changes as they occur, and simplifies the integration logic because the external system doesn’t need to maintain its own change-detection mechanisms.

Pre-Built Connectors

For common integration scenarios — major e-commerce platforms, common carrier networks, standard EDI formats, popular payment processors — cloud ERP vendors often provide pre-built connectors that handle the standard data mapping and communication protocols. These connectors reduce implementation effort and, critically, are maintained by the vendor as part of the platform. When the ERP updates, the connectors update with it.

The maintainability of pre-built connectors is their most valuable characteristic. Custom point-to-point integrations require ongoing maintenance by your team or a consultant whenever either system changes. Vendor-maintained connectors shift that maintenance burden to the platform team, which reduces long-term integration cost and eliminates a common source of post-launch operational surprises.

Why Architecture Should Be at the Top of Your Evaluation

Features get the attention. Architecture determines the outcome.

The features a vendor demonstrates in a 60-minute demo represent a fraction of the system’s surface area. The architecture underneath — how data is stored, how transactions process, how updates deploy, how the system scales, how security operates — determines whether those features perform reliably at scale, whether the system improves over time, and what it actually costs to operate over five and ten years.

Asking architectural questions during vendor evaluation isn’t technical overreach. It’s due diligence. Is the platform cloud-native or cloud-migrated? Unified data or modular? Multi-tenant or single-tenant? Continuously deployed or version-based? API-first or integration-by-afterthought? The answers to these questions predict your long-term experience with the platform more accurately than any feature comparison matrix.

How Bizowie Is Architected

Bizowie was designed from the ground up as a cloud-native, multi-tenant platform built on a unified data architecture. Every design decision — from the data layer to the integration framework to the deployment pipeline — was made with the understanding that the architecture determines the experience.

Our unified data model means every transaction posts once to a single data layer and is immediately visible across the entire system. No batch processing. No module silos. No reconciliation. When your warehouse scans a receipt, your purchasing team, your finance team, and your available-to-promise calculations all reflect it in the same moment.

Our multi-tenant architecture means every customer runs on the same continuously updated platform. Updates deploy incrementally and frequently, with zero customer action required. The platform you’re running today is always the current version — and it’s always getting better.

Our API-first integration architecture means your ERP connects to your e-commerce platforms, EDI partners, carriers, and other systems through standardized, documented interfaces that we maintain as part of the platform.

And we built all of this specifically for distribution businesses — the data model, the workflow engine, the transaction processing, the integration layer — all designed around the operational reality of companies that buy, warehouse, and ship physical products.

See the architecture in action. Schedule a demo with Bizowie and we’ll show you how cloud-native architecture, unified data, and continuous deployment translate into real-time visibility and operational control for your distribution business. The technology works. The experience proves it.