Distribution ERP vs. Generic ERP: Why Distributors Need Specialized Systems

The demo looked perfect. The sales team showed how the ERP handled orders, tracked inventory, managed purchasing, and generated reports. The reference customers spoke glowingly about their implementations. The ROI projections were compelling. So you signed the contract, spent eighteen months implementing, and now you’re discovering what generic ERP vendors don’t mention: the system wasn’t designed for how distributors actually operate.

Your warehouse team complains that the picking process requires workarounds that add minutes to every order. Your purchasing manager maintains spreadsheets because the system can’t handle your supplier rebate structures. Your customer service representatives toggle between screens to assemble information that should appear in one view. Your operations director spends weekends building custom reports because the standard analytics don’t address distribution questions. And every new requirement triggers a customization project with associated costs and timelines.

This is the generic ERP trap that catches distributors who don’t recognize that distribution is fundamentally different from manufacturing, retail, or service businesses. The ERP that works brilliantly for a manufacturer—tracking production schedules, managing bills of materials, calculating production costs—becomes a constant source of friction when applied to distribution operations. The platform that serves retailers well—managing point-of-sale, consumer promotions, and store operations—misses entirely what distributors need. And the “industry-neutral” system that claims to serve everyone actually serves no one particularly well.

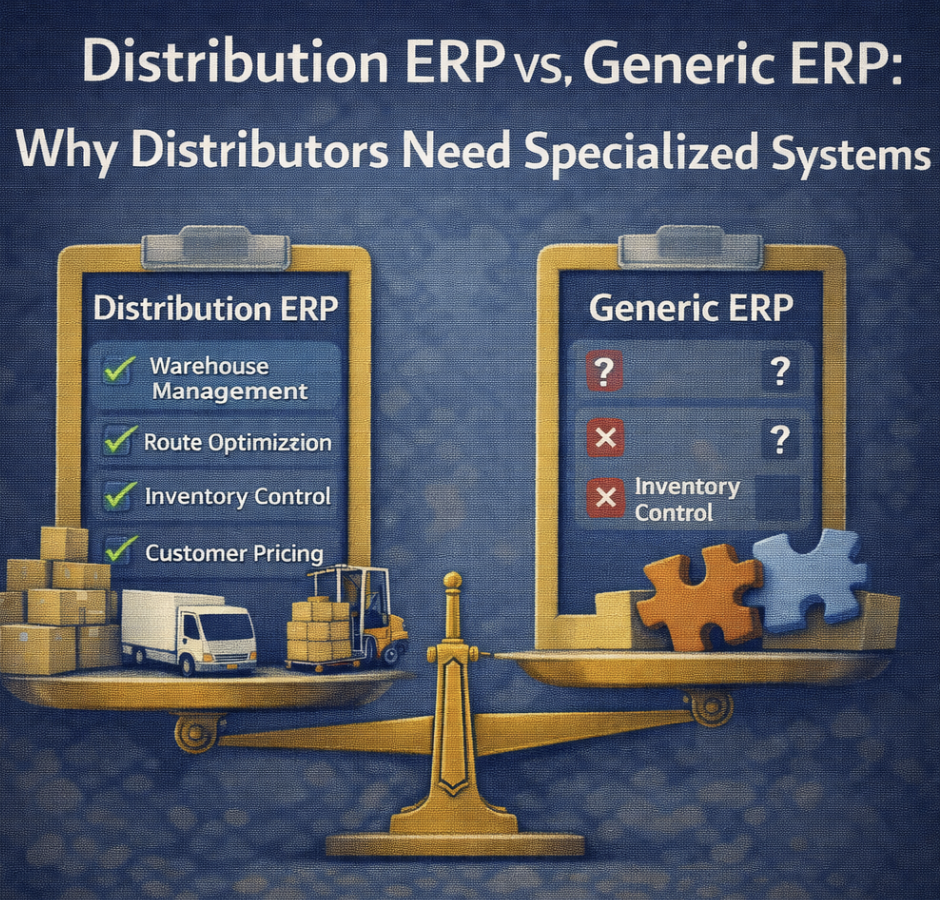

The difference between generic and distribution-specific ERP isn’t feature depth—it’s fundamental design philosophy. Distribution operations have unique characteristics that require purpose-built systems, not adapted general-purpose platforms.

What Makes Distribution Fundamentally Different

Distribution operations differ from manufacturing, retail, and service businesses in ways that determine what ERP systems must do well. These differences aren’t edge cases requiring occasional accommodation—they’re core operational patterns that run through every transaction.

Inventory is the product, not a component of production. Manufacturers transform raw materials into finished goods; their ERP focuses on production scheduling, bill-of-materials management, and work-in-process tracking. Distributors buy finished goods and resell them; their ERP must excel at inventory management, demand forecasting, and replenishment optimization. A manufacturing ERP treats inventory as input to production. A distribution ERP treats inventory as the asset that generates all revenue—a fundamentally different orientation that shapes every system function.

Customer relationships involve complex pricing, not simple transactions. Retailers sell to consumers at posted prices with occasional promotions. Distributors negotiate customer-specific pricing, volume discounts, contract terms, rebate structures, and special arrangements that vary by customer, product, and relationship history. A distribution ERP must handle pricing complexity that would never occur in retail—matrix pricing, tiered discounts, promotional overlays, customer-specific costs, and margin requirements that vary by product category and account type.

Order fulfillment spans multiple channels and locations. Distributors fulfill orders from multiple warehouses, ship via multiple carriers, support multiple delivery methods, and serve customers through multiple channels—all for the same customer, sometimes on the same order. Generic ERP systems often assume single-location fulfillment or simple shipping scenarios. Distribution ERP must orchestrate multi-location inventory visibility, intelligent order routing, split shipment management, and carrier optimization across complex fulfillment networks.

Supplier relationships are strategic, not transactional. Distributors depend on supplier relationships for product availability, pricing competitiveness, and market access. These relationships involve negotiated terms, volume commitments, rebate programs, co-op marketing, exclusive territories, and performance expectations that generic ERP doesn’t contemplate. Distribution ERP must manage supplier relationships as strategic assets, tracking performance, optimizing purchasing, and maximizing the value of supplier partnerships.

Demand patterns are volatile and customer-driven. Unlike manufacturers who can level-load production or retailers with relatively predictable consumer traffic, distributors face demand volatility driven by their customers’ businesses. A contractor’s project schedule, a manufacturer’s production surge, a retailer’s promotion—all create demand spikes that distributors must anticipate and serve. Distribution ERP requires sophisticated demand sensing, safety stock optimization, and inventory positioning capabilities that generic systems rarely provide.

Margins are thin and operationally determined. Distribution margins typically run 15-25% gross, with net margins in single digits. At these margins, operational efficiency determines profitability. The warehouse labor cost per order, the freight expense per shipment, the carrying cost per inventory dollar—these operational factors determine whether the business makes money. Distribution ERP must optimize operations with precision that fat-margin businesses don’t require.

Lot tracking, serialization, and traceability matter. Many distributors handle products requiring lot tracking for quality, expiration, or recall management. Others manage serialized products for warranty, service, or regulatory compliance. Some face traceability requirements for food safety, pharmaceutical distribution, or hazardous materials. Generic ERP systems often treat these as add-on modules rather than core capabilities integrated throughout transaction processing.

Unit-of-measure complexity is routine. Distributors routinely handle products sold in different units than purchased: cases bought, eaches sold; pallets received, cartons shipped; drums purchased, gallons dispensed. The conversions, pricing implications, and inventory accounting for unit-of-measure complexity are central to distribution operations. Generic ERP often struggles with these conversions or handles them through workarounds rather than native functionality.

These differences compound in their implications. A system designed around manufacturing assumptions will force distribution operations into uncomfortable accommodations at every turn. A platform built for retail will miss the B2B relationship complexity that defines distribution. Only systems designed specifically for distribution—with these operational patterns as foundational assumptions rather than edge cases—provide the fit that efficient operations require.

The Hidden Costs of Generic ERP in Distribution

When distributors implement generic ERP systems, the mismatch between system design and operational needs creates costs that persist throughout the system’s lifetime. These costs often exceed the apparent savings that made generic ERP attractive initially.

Customization expenses accumulate continuously. Generic ERP systems require customization to handle distribution-specific requirements—and the customization never ends. Handling customer-specific pricing requires custom development. Supporting lot tracking across transactions requires custom modules. Managing supplier rebates requires custom calculations. Each business requirement that falls outside generic assumptions triggers another customization project. Companies report spending 40-60% of initial implementation cost on customizations over the first five years—often more than the cost difference between generic and distribution-specific platforms.

Upgrade complexity and cost escalate over time. Every customization creates technical debt that complicates future upgrades. When the vendor releases new versions, custom code must be reviewed, tested, and potentially rewritten to maintain compatibility. Companies with heavily customized generic ERP often skip upgrades entirely because the effort and risk are too high—leaving them on outdated software without security patches, performance improvements, or new capabilities. The upgrade that should take weeks extends to months or years; the cost that should be modest becomes enormous.

Training and adoption suffer from poor fit. When systems don’t match operational patterns, users must learn workarounds rather than intuitive workflows. Training takes longer because processes aren’t natural. Adoption suffers because users fight the system rather than leveraging it. Error rates increase because workarounds introduce complexity. The ongoing productivity drag from poor system fit typically runs 15-25% compared to operations on well-fitted platforms—a permanent efficiency tax.

Integration complexity multiplies. Generic ERP systems that can’t handle distribution requirements natively often lead companies to implement specialized point solutions—warehouse management systems, transportation management systems, pricing engines, demand planning tools—that require integration. Each integration creates maintenance burden, data synchronization challenges, and potential failure points. The “integrated” ERP becomes the hub of a complex best-of-breed architecture with all associated integration costs and risks.

Reporting and analytics require extensive development. Generic ERP systems provide generic reports that don’t address distribution-specific questions. What’s my true cost-to-serve by customer? Which products should I stock in which locations? How are supplier fill rates trending? What’s my inventory investment by velocity category? These distribution questions require custom report development in generic systems—development that’s ongoing because new questions continuously emerge. Distribution-specific platforms provide native analytics addressing these questions without custom development.

Operational inefficiency persists despite best efforts. When systems don’t support distribution workflows natively, inefficiency becomes permanent. The extra clicks required for customer-specific pricing. The multiple screens needed to view complete customer context. The manual processes compensating for missing functionality. The workarounds that experienced staff develop and new staff must learn. This inefficiency might seem minor on any individual transaction but accumulates across thousands of daily transactions into significant productivity drag.

Opportunity costs from capability gaps. Generic ERP systems often lack capabilities that distribution operations would leverage if available. Advanced demand forecasting, intelligent inventory optimization, dynamic pricing, automated replenishment, predictive analytics—features that distribution-specific platforms provide natively often don’t exist or require expensive add-ons in generic systems. The business value these capabilities would create represents ongoing opportunity cost.

Vendor support limitations for distribution issues. When problems arise that relate to distribution-specific functionality, generic ERP vendors often can’t provide effective support. Their expertise is in their core platform, not distribution operations. Their customer base is diverse, so distribution-specific issues are lower priority. Their roadmap is driven by broad market needs, not distribution requirements. Distributors on generic platforms frequently find themselves without vendor support for their most pressing system challenges.

The total cost of ownership for generic ERP in distribution environments typically runs 30-50% higher than distribution-specific platforms when accounting for customization, integration, inefficiency, and opportunity costs—even when initial licensing costs are lower. The apparent savings from choosing generic platforms prove illusory when full lifetime costs are calculated.

What Distribution-Specific ERP Provides

Distribution-specific ERP platforms are designed from the ground up around distribution operational patterns. The difference isn’t additional features bolted onto generic platforms—it’s foundational architecture that assumes distribution operations as the primary use case.

Native multi-location inventory management treats inventory across locations as unified operational concern. Real-time visibility into stock levels at all warehouses, distribution centers, and forward stocking locations. Intelligent available-to-promise calculation considering inventory position across the network. Transfer order management for inter-branch stock balancing. Multi-location demand forecasting and replenishment optimization. These capabilities are core architecture, not add-on modules.

Sophisticated pricing engines handle the complexity that B2B distribution requires. Customer-specific pricing at item level. Volume discount structures with multiple tier definitions. Contract pricing with effective dates and terms. Promotional pricing with overlay logic. Matrix pricing by customer segment and product category. Margin requirements by product line. Real-time price calculation during order entry with visibility into applied rules. This pricing complexity is routine in distribution but exceptional in generic platforms.

Distribution-optimized warehouse management supports picking, packing, and shipping workflows designed for distribution throughput. Directed putaway that optimizes warehouse space and pick efficiency. Wave-based picking with intelligent work allocation. Zone picking with consolidation workflows. Cartonization and packaging optimization. Shipping workstation integration with carrier systems. These workflows assume distribution operations, not manufacturing or retail patterns.

Purchasing and supplier management built for distribution relationships. Purchase order management with blanket orders, scheduled releases, and vendor-managed inventory support. Supplier performance tracking across delivery, quality, and cost dimensions. Rebate and allowance management with automatic calculation. Cost tracking including freight, duties, and handling. Approved vendor lists by item. The strategic supplier relationship that distribution requires, not just transactional procurement.

Lot tracking and serialization integrated throughout transaction processing. Lot assignment at receipt with attribute capture. Lot-specific inventory visibility and allocation. FIFO, FEFO, or configured consumption logic. Lot traceability forward and backward through the supply chain. Serial number tracking where required. Expiration date management with alerts. These capabilities run through all transactions, not as separate modules with integration requirements.

Advanced demand planning and forecasting designed for distribution patterns. Statistical forecasting using distribution-appropriate algorithms. Demand sensing from current transaction patterns. Seasonal adjustment and promotional lift factors. New product introduction forecasting. Collaborative forecasting with customer input. Forecast accuracy measurement and continuous improvement. The demand volatility that distribution faces requires forecasting sophistication that generic platforms rarely provide.

Distribution-specific analytics and reporting address questions distributors actually ask. Inventory investment analysis by velocity, category, and location. Customer profitability including cost-to-serve factors. Supplier scorecard with performance metrics. Fill rate analysis by customer segment. Gross margin return on inventory investment. These reports exist natively, not as custom development requirements.

Order management designed for distribution complexity. Customer-specific product catalogs and availability. Order promising against real-time multi-location inventory. Backorder management with substitution logic. Split shipment handling with customer preferences. Standing order and blanket release support. The order management complexity that B2B distribution requires—not the simple order capture that generic systems assume.

Integrated customer relationship management connecting sales activity with operational execution. Customer hierarchy for pricing and credit. Contact management with role-based information. Sales territory and quota management. Opportunity tracking with quote generation. Customer-specific notes and handling instructions visible throughout operations. The customer relationship context that distribution sales requires, integrated with operational systems rather than separately maintained.

Mobile capabilities designed for distribution workflows. Warehouse receiving and putaway on handheld devices. Pick, pack, and ship workflows on mobile. Cycle counting with guided counting processes. Delivery confirmation with signature capture. Sales representative access to customer information and order entry. Mobile capabilities assume distribution operations rather than adapting generic mobile frameworks.

The cumulative effect is a platform that fits distribution operations without forcing operational accommodation to system limitations. Workflows feel natural because they were designed for distribution patterns. Capabilities exist natively because they were built for distribution requirements. The system accelerates operations rather than constraining them.

Industry-Specific Variations: Why Vertical Matters Within Distribution

Distribution itself encompasses diverse verticals with distinct operational characteristics. The best distribution-specific ERP platforms accommodate these variations rather than forcing one-size-fits-all approaches.

Food and beverage distribution requires capabilities around freshness, temperature, and food safety. Lot tracking with production and expiration dates. FEFO allocation ensuring oldest product ships first. Temperature zone management for cold chain. Catch weight handling for variable weight products. Food safety documentation for FSMA compliance. Recall management with rapid lot tracing. These requirements are non-negotiable for food distributors but irrelevant for others.

Building materials distribution emphasizes project management and contractor relationships. Project-based pricing and ordering. Multi-phase delivery scheduling aligned with construction timelines. Will-call and customer pickup workflows. Lumber tally and dimensional product handling. Contractor account management with job cost tracking. Returns handling for project overages. The construction industry’s buying patterns shape operational requirements.

Industrial supply distribution requires breadth and availability for MRO items. Massive SKU counts with long-tail demand patterns. Bin management for small parts. Vendor-managed inventory for strategic customers. Contract pricing for national accounts. Technical product data management. Emergency order handling for production-critical items. The industrial buyer’s urgency and breadth requirements define operational priorities.

Electrical distribution involves complex product relationships and compliance requirements. Configured products with customer-specific specifications. Pricing complexity across manufacturers and customer segments. Contractor licensing verification. Cut-to-length wire and cable handling. Lighting fixture configuration. Project pricing with labor estimates. The electrical trade’s technical requirements and project orientation shape system needs.

HVAC distribution balances equipment sales with parts and service support. Seasonal demand patterns requiring inventory positioning. Equipment configuration and compatibility. Warranty tracking and parts availability. Contractor program management. Service parts availability for emergency repairs. The combination of project equipment and ongoing parts support creates distinct operational patterns.

Pharmaceutical and medical supply distribution demands regulatory compliance throughout operations. DEA license verification and controlled substance tracking. Lot traceability for patient safety. Temperature monitoring for biologics. DSCSA compliance for drug supply chain security. Customer credentialing verification. The regulatory environment defines operational requirements that other verticals don’t face.

Chemical distribution involves hazardous materials management and compliance. Hazmat classification and shipping restrictions. Container and drum management. Material safety data sheet distribution. Environmental compliance documentation. Lot tracking for quality and regulatory requirements. The safety and compliance dimensions shape every operational process.

Automotive parts distribution emphasizes application lookup and obsolescence management. Vehicle application data for part lookup. Core management for remanufactured parts. Supersession chains for obsolete parts. Catalog integration with manufacturers. Return management for warranty cores. The automotive aftermarket’s application complexity and rapid obsolescence drive specific requirements.

The best distribution-specific ERP platforms provide core distribution functionality that all verticals need while accommodating the variations that make each vertical unique. This isn’t through heavy customization but through configurable capabilities that adapt to vertical requirements. Distributors should evaluate platforms not just for distribution fit generally but for specific vertical fit that matches their operational reality.

Evaluating Distribution ERP: What to Look For

Selecting distribution-specific ERP requires evaluation approaches that reveal true distribution fit rather than demo-polished generic capabilities. The evaluation process should surface whether platforms genuinely support distribution operations or just claim to.

Start with your hardest problems. Rather than evaluating standard order-to-cash flows, begin demonstrations with your most complex scenarios: the pricing structure that’s difficult to maintain, the warehouse workflow that’s inefficient, the reporting requirement you can’t satisfy, the customer situation that creates constant exceptions. How systems handle your hardest problems reveals their true distribution capability. Generic platforms fail these tests; distribution-specific platforms address them natively.

Evaluate pricing engine depth. Request demonstrations of complex pricing scenarios: customer-specific item pricing, volume discount tiers, promotional overlays, contract terms, margin requirements, and real-time price calculation during order entry. Ask to see how pricing rules are maintained—by business users through configuration or by developers through code. Ask how pricing changes are managed across customer segments. Pricing complexity is fundamental to distribution; how platforms handle it reveals distribution orientation.

Test multi-location inventory visibility. Demonstrate available-to-promise across multiple locations with committed orders, incoming supply, and transfer considerations. Show how orders are allocated when inventory is constrained. Display real-time inventory position across all locations in single view. Reveal how inter-branch transfers are recommended and managed. Multi-location inventory orchestration is core distribution requirement; platforms should handle it natively.

Examine lot tracking integration. For distributors requiring lot management, evaluate how lots flow through all transactions—receiving, putaway, picking, shipping, returns, adjustments. Ask how lot selection occurs during allocation: FIFO, FEFO, or customer-specific requirements. Request demonstration of forward and backward traceability from any lot. Lot tracking should be seamlessly integrated, not a separate module requiring special handling.

Assess warehouse workflow fit. Observe demonstrations of receiving, putaway, picking, packing, and shipping workflows. Do they match your operational patterns or require adaptation? Can workflows be configured for your specific processes? Are mobile capabilities native to the platform or bolted-on additions? Distribution warehouse operations have specific patterns; platforms should support them without forcing procedural changes.

Verify reporting and analytics nativity. Ask for demonstrations of standard reports addressing distribution questions: inventory investment analysis, customer profitability, supplier performance, fill rates, demand patterns. How quickly are these reports available? Are they real-time or based on overnight extracts? Can they be modified without custom development? Native distribution analytics reveal platform orientation; requirements for custom development reveal generic foundations.

Examine upgrade and maintenance paths. Ask how customizations affect upgrades. What’s the typical upgrade process and timeline? How are customer-specific configurations preserved across versions? What technical debt accumulates over time? Platforms designed for distribution should support configuration without creating upgrade obstacles. Heavy customization requirements suggest generic platforms requiring adaptation.

Request distribution-specific references. Ask for references from distributors in your specific vertical. Not manufacturers using the platform, not retailers, not service companies—distributors facing similar operational challenges. Speak directly with operational users, not just IT staff or executives. Ask what works well, what required customization, and what still doesn’t fit. Authentic distribution references reveal true platform fit.

Evaluate vendor distribution expertise. Assess whether the vendor understands distribution operations. Do their implementation consultants have distribution experience? Is their roadmap driven by distribution requirements? Do they participate in distribution industry associations? Are their documentation and training materials distribution-oriented? Vendor expertise matters because implementation quality depends on understanding your operational context.

Calculate true total cost of ownership. Beyond licensing costs, estimate customization requirements, integration needs, training time, ongoing maintenance, and operational efficiency impacts. Compare platforms on total cost over five years, not just initial purchase price. Distribution-specific platforms often have higher licensing costs but lower total cost when customization, integration, and efficiency factors are included.

The evaluation process should conclusively determine whether platforms are genuinely distribution-oriented or merely claim distribution capability through marketing rather than architecture. The difference becomes apparent only through rigorous evaluation focused on distribution-specific requirements.

The Migration Decision: When to Move from Generic to Distribution-Specific

Distributors currently running generic ERP face complex decisions about whether and when to migrate to distribution-specific platforms. The decision involves both strategic and operational considerations.

Recognize the status quo isn’t free. The cost of continuing on a generic platform includes ongoing customization, integration maintenance, operational inefficiency, and capability limitations. These costs should be quantified and compared against migration investment. Often, the cost of staying exceeds the cost of moving when calculated over three to five years.

Evaluate strategic constraints from current platform. What capabilities does your current platform prevent? Can you implement modern warehouse automation? Can you provide customer self-service portals? Can you support omnichannel sales? Can you optimize inventory investment? Strategic limitations from platform constraints should factor into migration decisions alongside operational costs.

Assess upgrade pathway on current platform. If you’re facing major version upgrades on your current generic platform, the upgrade investment might approach migration investment. If customizations make upgrades prohibitively expensive, you’re effectively on end-of-life software regardless of vendor claims. The upgrade decision point is often the natural time for platform evaluation.

Consider acquisition and growth implications. If your strategic plan includes acquisitions, growth into new markets, or significant operational expansion, evaluate whether your current platform can support these initiatives. Generic platforms often become barriers to growth as complexity increases. Migration before growth is easier than migration during growth.

Evaluate staff capacity and capability. Migration requires organizational capacity for implementation alongside continuing operations. If your team is already stretched maintaining current systems, adding migration may not be feasible without additional resources. Conversely, if you’re about to lose key staff with institutional knowledge of your customized generic platform, migration may be urgent before that knowledge disappears.

Plan for operational continuity during transition. Migration doesn’t require big-bang replacement. Modern distribution platforms often support phased implementation—migrating core operations first, then extending to additional capabilities. Parallel operation during transition periods provides fallback options. The migration approach should minimize operational risk while achieving strategic objectives.

Time migration relative to business cycles. Avoid go-live during peak seasons or other periods of maximum operational stress. The best migration timing provides stable operations during implementation, adequate time for training and adjustment before critical periods, and organization capacity for change management alongside continuing business.

Build the business case on comprehensive analysis. Migration decisions should be supported by detailed analysis of current platform costs (including hidden costs of customization, inefficiency, and capability limitations), distribution platform benefits (both efficiency gains and capability enablement), implementation investment and timeline, risk factors and mitigation approaches, and ROI projections with sensitivity analysis. The decision is significant enough to warrant rigorous analytical support.

The migration decision often crystallizes around specific triggering events: upcoming major upgrades on current platforms, departure of key technical staff, strategic initiatives blocked by platform limitations, or accumulating operational frustration reaching critical threshold. Distributors should proactively evaluate their platform situation rather than waiting for crisis to force decisions.

The Strategic Case for Distribution-Specific ERP

Beyond operational efficiency and cost considerations, distribution-specific ERP platforms enable strategic capabilities that generic systems cannot provide. These strategic dimensions often prove more valuable than operational improvements.

Customer experience differentiation becomes achievable when systems support distribution-specific interactions. Customer portals showing real-time inventory availability, order status, invoice history, and account information—all reflecting the pricing, product availability, and relationship context specific to each customer. Self-service capabilities for order entry, reorder, and account management. Mobile access for customer staff. These experiences differentiate distributors in competitive markets and create switching barriers that protect relationships.

Operational agility for market response enables pursuing opportunities that rigid platforms prevent. Adding new product lines without system projects. Entering new geographic markets without infrastructure expansion. Acquiring competitors without years of integration. Launching new sales channels without custom development. Distribution-specific platforms designed for flexibility enable strategic moves that generic platforms’ rigidity prevents.

Data-driven decision making becomes practical when systems generate distribution-relevant analytics. Inventory optimization across the network based on demand patterns and service level requirements. Customer prioritization based on profitability and potential. Supplier selection based on total cost including quality, service, and reliability. Pricing optimization based on competitive position and margin objectives. Strategic decisions informed by accurate, relevant analytics improve business outcomes.

Talent attraction and retention improves when systems are tools rather than obstacles. Distribution professionals prefer working with systems that support their expertise rather than fighting systems that impede their effectiveness. Modern distribution platforms attract staff who expect modern technology experiences. Organizations known for operational excellence through technology advantage have recruiting advantages in competitive talent markets.

Sustainable competitive advantage develops when operational capabilities compound over time. Distribution-specific platforms enable continuous improvement in ways generic platforms cannot. Each year of operation on fitted platforms builds capabilities—optimized processes, refined analytics, accumulated operational intelligence—that competitors on generic platforms cannot match. The capability gap widens over time, creating durable competitive advantage.

Business valuation impact reflects operational excellence enabled by appropriate platforms. Acquirers and investors recognize that distribution operations on modern, distribution-specific platforms are more valuable than those struggling with generic system limitations. Clean operations, reliable data, scalable systems, and efficient processes command valuation premiums. Technology platform quality directly impacts enterprise value.

The strategic case for distribution-specific ERP extends beyond the operational improvements and cost savings that justify implementation. These platforms enable strategic capabilities, market responsiveness, talent attraction, and competitive positioning that determine long-term business success—dimensions that generic platforms fundamentally cannot support.

Making the Distribution ERP Decision

The choice between generic and distribution-specific ERP is among the most consequential technology decisions distributors face. The platform selected will shape operations, constrain or enable strategy, and influence competitive position for years after implementation.

The appeal of generic platforms is understandable: familiar vendor names, broad market presence, apparent flexibility, and sometimes lower initial costs. But these advantages prove illusory when distributors discover that generic platforms require endless customization to handle distribution operations, create technical debt that complicates upgrades and maintenance, impose operational inefficiency through poor workflow fit, lack analytics and capabilities that distribution operations need, and constrain strategic initiatives through platform limitations.

Distribution-specific platforms designed around distribution operational patterns eliminate these compromises. Native capabilities for multi-location inventory management, complex pricing, lot tracking, demand forecasting, warehouse operations, and supplier management—built as foundational architecture rather than add-on modules. Workflows that match how distributors actually operate. Analytics that address questions distributors actually ask. Roadmaps driven by distribution requirements rather than diverse market needs.

The total cost of ownership analysis typically favors distribution-specific platforms despite sometimes higher initial licensing costs. When customization, integration, operational efficiency, and strategic capability factors are included, distribution-specific platforms deliver better value over platform lifetime. The apparent savings from generic platforms disappear when full costs are calculated.

For distributors evaluating ERP platforms, the critical question isn’t which system has the most features or the lowest price—it’s which system was designed for how you actually operate. The platform that fits distribution operations natively will outperform generic alternatives on every meaningful dimension: implementation efficiency, operational effectiveness, strategic enablement, and long-term value.

For distributors ready to implement platforms designed specifically for their operational reality, Bizowie delivers the distribution-specific ERP that modern distribution demands. Our platform was built from the ground up around distribution operations—not adapted from manufacturing or retail systems, not generalized for diverse markets, but purpose-built for how distributors actually work. Native multi-location inventory management, sophisticated pricing engines, distribution-optimized warehouse management, integrated lot tracking, advanced demand forecasting, and distribution-specific analytics—all as foundational architecture rather than customization requirements.

Schedule a demo to see how Bizowie’s distribution-specific approach eliminates the compromises that generic platforms impose, or explore how purpose-built architecture enables operational excellence that adapted systems cannot deliver.