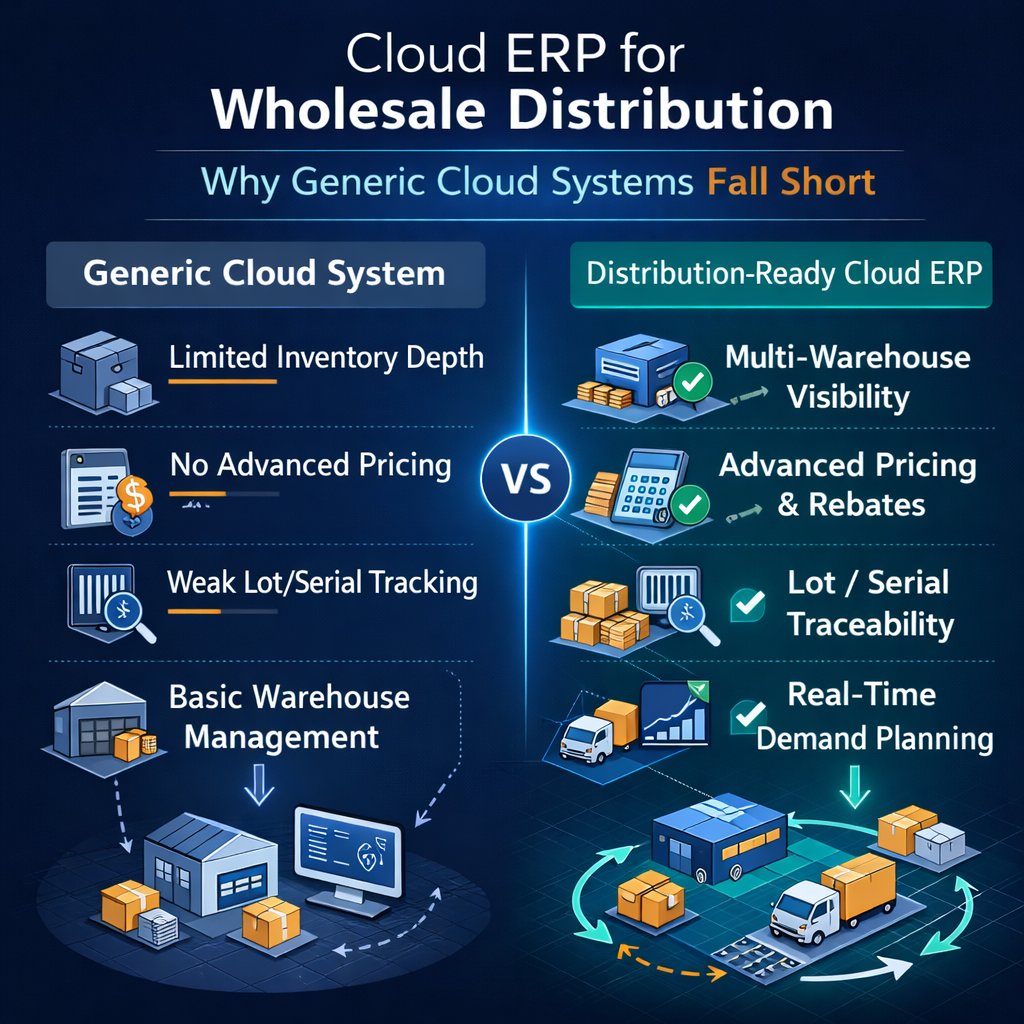

Cloud ERP for Wholesale Distribution: Why Generic Cloud Systems Fall Short

Wholesale distribution is a business of margins, velocity, and precision. You buy in bulk, you warehouse strategically, you sell across channels with pricing structures that would make a mathematician pause, and you ship with accuracy and speed that your customers treat as a given — until you miss. The entire operation runs on the ability to move the right product to the right place at the right time at the right price, and the margin for error is measured in pennies per unit and minutes per order.

Generic cloud ERP systems don’t understand this. They weren’t built for it.

They were built for a theoretical business that does a little of everything — some manufacturing, some services, some project management, some distribution, some retail — and does none of it with the depth that wholesale distribution demands. The features exist on the checklist. They demo well enough. But when a wholesale distributor tries to run a real operation on a generic platform, the gaps appear in the first week and compound every week after.

This article explains why wholesale distribution is different, where generic platforms fail, and what a purpose-built cloud ERP actually delivers when it’s designed around the realities of the distribution business.

What Makes Wholesale Distribution Different

Every industry thinks it’s unique. Distribution actually is — not because the individual processes are exotic, but because the combination, the volume, the speed, and the margin structure create operational demands that generic systems weren’t designed to handle.

Margin Compression Demands Operational Precision

Wholesale distribution operates on margins that leave no room for inefficiency. Gross margins of 15% to 25% are typical, and net margins are often in the low single digits. At these margins, a mispick, an incorrect price, a missed discount threshold, or an unnecessary truck roll doesn’t just cost money — it can erase the profit on an entire order.

This margin reality means the ERP isn’t just a management tool. It’s the operational engine that determines whether individual transactions are profitable. Every function the system performs — pricing a line item, allocating inventory, routing a shipment, calculating a landed cost — either protects the margin or erodes it. Generic platforms that handle these functions at a surface level produce surface-level accuracy, and in a business where the difference between profit and loss lives in the details, surface-level accuracy isn’t accurate enough.

Volume and Velocity Are the Norm, Not the Exception

A wholesale distributor processing 500 to 5,000 orders per day isn’t operating in peak mode — that’s Tuesday. The system needs to handle this volume not as a stress test but as a baseline, with the headroom to absorb seasonal spikes, promotional surges, and new customer onboarding without degradation.

This isn’t just a hardware question — though elastic cloud infrastructure helps. It’s an application design question. The workflows, the allocation algorithms, the pricing engine, the warehouse direction logic, and the integration layer all need to be architected for throughput. A system designed for a company that processes 50 orders a day and then asked to handle 2,000 doesn’t just slow down. It breaks — in the allocation queue, in the pick optimization, in the shipping integration, in the invoice generation, or in the reporting that’s trying to aggregate it all.

Pricing Is a Competitive Weapon, Not a Data Entry Field

In wholesale distribution, pricing isn’t a lookup table. It’s a strategic function that varies by customer, by product, by volume, by contract, by season, by channel, and sometimes by the mood of the market on a given Tuesday.

A single customer might have a negotiated contract price on 200 SKUs, volume-tiered pricing on another 500, a cost-plus arrangement on specialty items, and standard list pricing on everything else — with promotional overrides layered on top of all of it during certain periods. Multiply that by hundreds or thousands of customers, and the pricing matrix becomes one of the most complex data structures in the business.

Generic ERP platforms handle pricing as a secondary feature because most industries don’t need this depth. They offer list prices, basic discount schedules, and maybe customer-specific overrides for a limited number of products. When a distributor tries to implement their actual pricing reality, the system either can’t accommodate it or requires extensive customization that creates technical debt and upgrade risk.

Inventory Is the Business

For manufacturers, inventory is a component of production. For retailers, inventory is a cost of sales. For wholesale distributors, inventory is the business itself. The entire operation exists to have the right product in the right location at the right time — and the cost of getting it wrong flows in both directions. Too much inventory ties up capital, consumes warehouse space, and creates obsolescence risk. Too little inventory means stockouts, lost sales, expedited freight, and damaged customer relationships.

Managing this balance requires inventory visibility and intelligence that generic systems can’t provide. Real-time available-to-promise across every location. Demand-driven replenishment that responds to actual consumption rather than static reorder points. Lot and expiration tracking for perishable or regulated products. Inventory valuation methods — FIFO, LIFO, average cost, specific identification — that match your financial and operational requirements. Inter-warehouse transfer management that optimizes network-wide inventory positioning.

Each of these capabilities exists at some level in most ERP platforms. The question is whether they exist with the depth and integration required to actually manage a distribution inventory operation, or whether they’re checkbox features that handle simple scenarios and fall apart at scale.

The Warehouse Is a Revenue Engine

In distribution, the warehouse isn’t a cost center that stores things. It’s a revenue engine that fulfills promises. Warehouse speed and accuracy directly determine customer satisfaction, order-to-cash cycle time, and the company’s ability to compete on delivery.

This means warehouse management in a distribution ERP isn’t a supporting module — it’s a core operational capability. Directed receiving and putaway that optimizes storage locations. Pick methodologies — wave picking, zone picking, batch picking, discrete picking — matched to order profiles and warehouse geography. Lot control and serial tracking throughout the warehouse workflow. Cycle counting programs that maintain inventory accuracy without shutting down operations. Cross-docking for products that should flow through the warehouse rather than sit in it. And mobile execution on RF scanners and tablets that keeps warehouse associates moving rather than walking back to a terminal for every transaction.

Generic ERP systems typically offer basic warehouse functionality — location tracking, simple pick lists, inventory adjustments — that works for a company with one small warehouse and straightforward operations. A wholesale distributor with multiple warehouses, thousands of SKUs, complex storage requirements, and a fulfillment operation where minutes matter needs capabilities that go several layers deeper.

Trading Partner Relationships Are Systemically Complex

Wholesale distributors operate at the center of supply chains, connecting manufacturers and suppliers with retailers, contractors, institutions, and other downstream customers. These relationships aren’t just commercial arrangements — they’re system-level integrations that require the ERP to communicate electronically with dozens or hundreds of trading partners.

EDI is the backbone of these relationships. Purchase orders flow in electronically. Advance ship notices flow out. Invoices exchange automatically. Compliance requirements — label formats, packing specifications, routing guides, document timing — vary by trading partner and carry financial penalties for non-compliance. A retailer that charges $500 per ASN violation can turn EDI compliance from a technology requirement into a margin protection imperative.

Generic ERP systems treat EDI as an edge case or a third-party integration. Distribution ERP systems treat it as a core workflow — because for wholesale distributors, it is.

Where Generic Cloud ERP Systems Fail Distributors

The failures aren’t dramatic. They’re death by a thousand cuts — small gaps and shallow implementations that force workarounds, consume labor, and prevent the distributor from operating at the speed and precision the business demands.

Pricing That Can’t Keep Up

This is usually the first pain point. The distributor implements the generic platform, configures the basic pricing structure, and immediately discovers that the pricing engine can’t accommodate their actual complexity. Customer-specific prices need to be maintained in a spreadsheet and manually applied. Volume tier calculations require workarounds. Contract pricing with date ranges and renewal logic doesn’t fit the system’s data model. Matrix pricing based on product attributes isn’t supported.

The workaround is always the same: someone in the office becomes the human pricing engine, checking spreadsheets and manually overriding system prices on complex orders. This works at low volume. It falls apart at 500 orders a day. And it creates an error rate that erodes margin on every incorrectly priced order.

Inventory Visibility That’s Hours Behind

Generic platforms that update inventory in batches — syncing warehouse data to the main system every few hours or overnight — create a gap between physical reality and system reality that distributors can’t afford. A salesperson checks availability and promises delivery, not knowing that the last 50 units were allocated to another order processed since the last sync. Purchasing places a replenishment order based on inventory levels that don’t reflect today’s receipts. The warehouse picks an order and discovers a discrepancy between what the system says is in the location and what’s actually there.

These aren’t edge cases in distribution. They’re daily occurrences on platforms where inventory doesn’t update in real time — and each one costs time, money, or customer trust.

Warehouse Functions That Don’t Direct Work

There’s a fundamental difference between a system that tracks what’s in the warehouse and a system that directs the work of the warehouse. Generic platforms do the former. Distribution operations need the latter.

Tracking tells you what’s on the shelf. Direction tells the associate where to go, what to pick, in what sequence, using what method, and confirms each step in real time. The difference in warehouse productivity between these two approaches isn’t incremental — it’s transformational. Directed warehouse execution reduces travel time, increases pick accuracy, accelerates throughput, and provides real-time visibility into warehouse performance that tracking-only systems can’t offer.

When a distributor implements a generic ERP and discovers that the warehouse module is essentially a digital version of a paper-based location system, they face a choice: supplement it with a standalone WMS that creates a separate system to manage and integrate, or accept the limitations and work around them. Neither option is good.

Order Management That Doesn’t Understand Distribution

Distribution order management isn’t just capturing what the customer wants to buy. It’s a complex decision engine that needs to evaluate inventory availability across locations, apply the correct pricing from multiple overlapping structures, check credit terms, determine fulfillment routing, handle partial shipments and backorders, manage drop-ship scenarios, and comply with customer-specific requirements — all before the order reaches the warehouse.

Generic platforms handle order entry. Purpose-built distribution platforms handle order management. The difference shows up in how many orders require manual intervention, how many pricing exceptions need human review, how many allocation decisions require someone to override the system, and how many fulfillment complications could have been handled automatically if the system understood distribution logic.

Reporting That Can’t Answer Distribution Questions

The questions a wholesale distributor needs to answer aren’t the questions a generic ERP was built to address. What’s my real margin on this customer after rebates, freight, and handling? Which SKUs are turning too slowly in which locations? What’s my vendor fill rate by supplier and product category? Where are my dead stock positions, and what’s the carrying cost? How does my actual landed cost compare to my standard cost by product line?

These questions require data that spans inventory, purchasing, sales, finance, and warehouse operations — and they require it in real time, not as a month-end report. On unified data architectures, these reports are straightforward because all the data lives in one place. On modular architectures, each question requires pulling from multiple databases, reconciling the results, and accepting the latency of whichever data source updated least recently.

EDI That’s an Afterthought

When EDI compliance is handled through a separate, third-party translation system that sits between the ERP and the trading partner network, every EDI transaction involves an extra system, an extra integration to maintain, and an extra point of failure. Inbound purchase orders need to flow from the translator into the ERP and trigger order management logic. Outbound ASNs and invoices need to flow from the ERP through the translator and comply with partner-specific formatting requirements.

This middleware layer adds cost, adds complexity, and introduces a maintenance burden that grows with every trading partner added. When the ERP updates, the EDI integration needs testing. When a trading partner changes their specifications, both the translator and the ERP may need configuration changes. The operational overhead of maintaining a separate EDI system alongside a generic ERP is one of the most underestimated costs in distribution technology.

What Purpose-Built Distribution ERP Delivers

The difference between a generic platform stretched to fit distribution and a platform built for distribution from the ground up shows in every workflow, every day.

Pricing That’s as Sophisticated as Your Business

A purpose-built distribution ERP handles the full pricing matrix natively. Customer-specific pricing for any number of customers and products. Volume-tier structures that calculate automatically as line quantities change. Contract pricing with effective dates, renewal logic, and automatic expiration. Matrix pricing that derives prices dynamically from product attributes rather than requiring static price records for every combination. Cost-plus calculations against real-time landed costs, not outdated cost snapshots. Promotional overlays with date ranges and eligibility rules. And all of it resolved automatically at order entry, so the correct price appears without manual intervention regardless of which pricing structure — or combination of structures — applies.

When the pricing engine handles complexity natively, your customer service team processes orders with confidence. Your margin on every transaction is protected by the system rather than dependent on human memory and spreadsheet lookups. And your pricing strategy can evolve as fast as the market requires because changing a pricing rule is a configuration task, not a development project.

Real-Time Inventory That’s Actually Real-Time

On a unified data architecture, every inventory event — receipt, allocation, pick, pack, ship, adjustment, transfer, return — posts to the system in the moment it occurs. Available-to-promise calculations reflect current reality across every location. Two salespeople checking availability at the same second see the same accurate position. Purchasing decisions are based on actual stock levels and actual demand, not approximations assembled from batch-processed snapshots.

This isn’t a premium feature layered on top of the standard platform. It’s a structural characteristic of the architecture — the inevitable result of a unified data model where every function operates on the same data in real time. You can’t have real-time inventory on a modular architecture without building real-time synchronization between modules, which is complex, expensive, and never quite as reliable as reading from a single source of truth.

Warehouse Management Built for Distribution Workflows

Advanced warehouse management designed for distribution handles the specific workflows that generic warehouse modules treat as edge cases. Directed putaway that assigns locations based on velocity, product characteristics, and space optimization. Pick methodologies matched to order profiles — wave picking for high-volume batch fulfillment, zone picking for large warehouses, discrete picking for complex or high-value orders. Lot tracking and serial control throughout the warehouse workflow, not just at receipt and shipment. Cycle counting programs that continuously validate inventory accuracy by zone, velocity, or ABC classification. Cross-docking workflows that route qualifying product directly from receiving to shipping.

This depth of warehouse functionality isn’t something every distributor needs from day one. A company with one warehouse and straightforward operations may operate effectively with core inventory management. But for distributors whose warehouse execution directly determines competitive position — where pick accuracy, fulfillment speed, and labor productivity are strategic metrics — advanced warehouse management is the difference between an operation that’s managed by the system and one that’s managed around it.

Order Management That Thinks Like a Distributor

Purpose-built distribution order management handles the complexity that generic systems force onto your team. Multi-source fulfillment that routes orders to the optimal warehouse based on inventory position, proximity, and customer preference. Automatic backorder management with configurable rules for notification, substitution, and partial shipment. Drop-ship orchestration that generates purchase orders to suppliers and routes fulfillment without the product touching your warehouse. Customer-specific compliance — packaging requirements, labeling specifications, routing guides — applied automatically based on the ship-to address and trading partner profile.

When order management understands distribution, the percentage of orders that flow through the system without manual intervention increases dramatically. And every order that processes automatically is an order that’s faster, cheaper, and less error-prone than one that required someone to intervene.

EDI as a Core Workflow

Native EDI processing means inbound documents — purchase orders, forecasts, planning schedules — parse, validate, and enter the order management workflow automatically. Outbound documents — invoices, advance ship notices, functional acknowledgments — generate from standard business events and format to trading partner specifications without middleware. Compliance requirements are managed within the system, with visibility into document status, error rates, and partner-specific performance.

No separate translation system. No additional integration to maintain. No middleware vendor to manage alongside the ERP vendor. EDI is just another transaction flowing through the same unified platform — which is exactly what it should be for a business where electronic trading is a condition of participation, not an optional capability.

Financial Integration That Eliminates the Reconciliation Burden

When finance operates on the same real-time data layer as inventory, purchasing, and sales, the perpetual reconciliation exercise that consumes distribution accounting teams disappears. Inventory receipts create financial accruals in the same transaction. Cost of goods sold reflects actual landed costs applied at the time of sale. Accounts payable matches against receiving data that’s already in the system. Revenue recognition triggers from shipment confirmation. And the general ledger reflects current operational reality at all times — not a version of reality that’s waiting for a batch process to catch up.

The month-end close accelerates because there’s nothing to reconcile. The financial picture is always current because it’s always connected. And the finance team spends less time chasing discrepancies and more time analyzing the business — which is where their expertise actually creates value.

The Build vs. Buy Decision in Distribution

Some distributors, faced with the shortcomings of generic ERP, consider building custom solutions — assembling a technology stack from point solutions, custom integrations, and bespoke development to create a system tailored to their exact requirements.

This path is understandable and almost always wrong.

Building a custom distribution technology stack means becoming a software company — maintaining code, managing integrations, handling security, planning infrastructure, and keeping the whole thing running while your actual business is buying and selling products. The initial development cost is just the beginning. The ongoing maintenance, the integration upkeep, the security patching, the scaling challenges, and the inevitable departure of the developers who built it create a technology burden that distracts from the business it was supposed to serve.

Purpose-built cloud ERP for distribution eliminates the need for this trade-off. The depth is already there. The integration is already built. The platform is already maintained, secured, and updated by a team whose entire job is making it work for distribution businesses. The build-versus-buy decision, for most wholesale distributors, is straightforward: buy the platform that was built for you.

How Bizowie Was Built for Wholesale Distribution

Bizowie wasn’t designed for a theoretical company that does a little of everything. It was designed for wholesale distributors — companies that live and die by inventory accuracy, fulfillment speed, pricing precision, and margin management.

The platform’s unified data architecture delivers real-time visibility across every dimension of the distribution operation. Pricing handles the full complexity that wholesale distribution demands — customer-specific, volume-tiered, contract-based, cost-plus, matrix — without customization and without spreadsheets. Order management thinks like a distributor, with multi-source fulfillment, backorder management, drop-ship orchestration, and customer-specific compliance built into the workflow. Native EDI processing handles electronic trading as a core function, not a bolted-on integration. Financial management is integrated at the data level, eliminating reconciliation and accelerating the close.

Advanced distribution capabilities — directed putaway, pick optimization, lot and serial tracking, cycle counting, cross-docking — are available as a dedicated module for operations that need that warehouse depth. And manufacturing capabilities are available for distributors that also produce or assemble.

Every capability runs on the same continuously updated, multi-tenant platform. Every capability is implemented directly by the team that built it. And every capability reflects the operational reality of wholesale distribution because that’s the business Bizowie was built to serve.

See what purpose-built distribution ERP looks like. Schedule a demo with Bizowie and bring your pricing complexity, your warehouse workflows, your EDI requirements, and your toughest operational scenarios. We built the platform for exactly this.