Does Cloud ERP Work for Complex Businesses? Why Simplicity Doesn’t Mean Simple

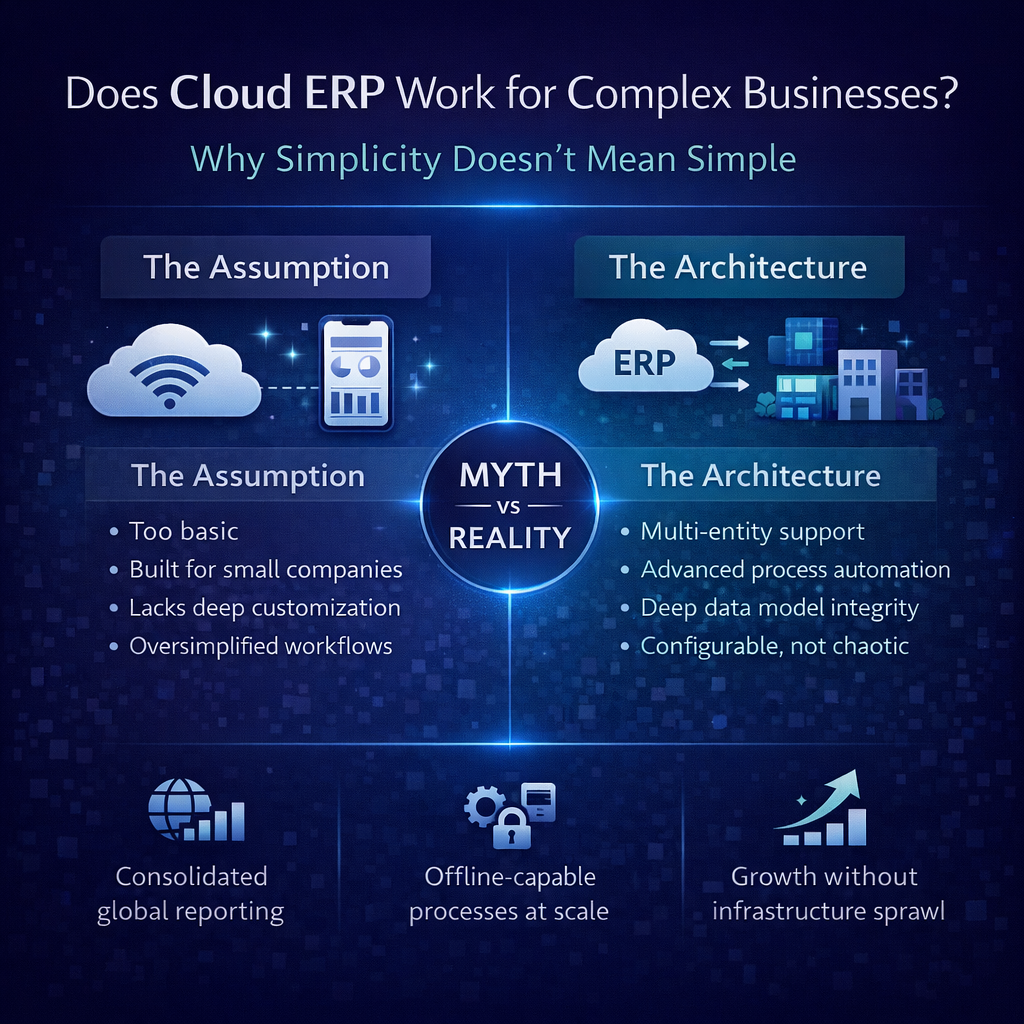

There’s a persistent assumption in enterprise software that complexity requires complexity. That if your business is operationally demanding — multi-warehouse distribution with thousands of SKUs, layered pricing structures, EDI compliance requirements, lot tracking, intricate fulfillment logic, and financial reporting that spans entities and locations — you need an equally demanding ERP system. One with hundreds of configuration screens. One that requires a team of consultants to implement. One that takes a year to deploy and another year to stabilize. One that’s so sophisticated it needs its own department to manage.

This assumption isn’t just wrong. It’s the most expensive misconception in enterprise software.

The vendors and consulting firms that profit from complexity have spent decades reinforcing the idea that a powerful system must be a painful system — that implementation difficulty is a proxy for capability, that consultant dependency signals enterprise-grade depth, and that if the software is easy to use, it must be cutting corners on functionality.

The reality is the opposite. The most capable platforms are the ones that handle complexity internally so they can present simplicity externally. The power is in the architecture. The simplicity is in the experience. And the companies that confuse a painful implementation with a powerful system end up paying enterprise prices for enterprise headaches while still running spreadsheet workarounds to compensate for the gaps.

This article is for the operations leaders and CFOs at complex distribution businesses who’ve been told — by vendors, by consultants, by their own IT departments — that their business is too complex for anything other than a traditional enterprise ERP engagement. It isn’t. But understanding why requires unpacking what complexity actually means and where it should live.

The Complexity Myth: Who Benefits From It

The idea that complex businesses need complex software serves a very specific set of interests, and those interests aren’t yours.

Systems integrators and consulting firms generate revenue proportional to implementation complexity. A system that takes 14 months to deploy generates more billable hours than one that takes 14 weeks. A platform that requires a consultant for every configuration change creates an annuity stream that persists for years after go-live. The consulting ecosystem doesn’t just tolerate complexity — it depends on it. Every layer of difficulty is a revenue opportunity. Simplifying the platform would simplify the consultants out of a job.

Enterprise ERP vendors have built their products over decades through acquisition and accumulation. They’ve bought manufacturing modules from one company, warehouse management from another, financial reporting from a third, and assembled them into a suite that’s marketed as “integrated” but is architecturally a collection of separate systems connected by middleware. The resulting complexity isn’t a feature — it’s a consequence of how the product was built. But these vendors can’t simplify without rebuilding from scratch, so they’ve reframed the complexity as depth and the difficulty as enterprise-grade capability.

IT departments sometimes have an institutional interest in complex systems because complex systems require IT to manage them. A self-service platform that operations can configure without IT involvement reduces IT’s organizational importance. This isn’t about bad intentions — most IT teams genuinely want to serve the business well. But the incentive structure of traditional ERP, where every change requires technical expertise, naturally positions IT as a gatekeeper rather than an enabler.

None of these interests are aligned with what the business actually needs, which is a system that handles operational complexity powerfully while being straightforward to implement, use, and evolve. That alignment — powerful and straightforward — is what the complexity myth exists to prevent you from believing is possible.

What “Complex” Actually Means in Distribution

When distribution companies describe themselves as complex, they’re usually referring to specific operational characteristics that their current systems handle poorly. It’s worth naming these explicitly, because the gap between what makes a distribution business genuinely complex and what makes an ERP system complex isn’t the same gap — and confusing the two is how companies end up with bloated implementations that still don’t solve their actual problems.

Pricing Complexity

Distribution pricing is legitimately complex. Customer-specific pricing for thousands of customers. Volume tiers that recalculate as line quantities change. Contract pricing with effective dates, renewal terms, and automatic expiration. Matrix pricing where the price is derived from product attributes rather than stored statically. Cost-plus calculations against landed costs that change with every purchase order. Promotional overlays with date ranges, eligibility rules, and stacking logic. Rebate programs that calculate retroactively based on period volume.

This is real complexity. But it’s complexity that belongs inside the pricing engine, not in the implementation project. A well-designed pricing engine handles all of this through configuration — define the customer price lists, set up the tier structures, create the contract terms, configure the matrix rules. The complexity lives in the logic. The experience is straightforward: enter an order, the price is correct. No spreadsheet lookup. No manual override. No phone call to a pricing manager.

When an ERP vendor tells you that your pricing complexity requires custom development, they’re admitting their pricing engine wasn’t built for distribution. They’re not describing a fundamental truth about the relationship between pricing complexity and system complexity.

Inventory Complexity

Multi-warehouse inventory with different storage types, different handling requirements, and different levels of operational sophistication at each location. Lot tracking for regulated or perishable products. Serial number management for high-value items. Multiple units of measure — buying by the case, storing by the pallet, selling by the each — with conversions that need to be automatic and accurate. Catch weights for products sold by weight where units vary. Expiration date management with FEFO picking logic. Consignment inventory managed on your premises but owned by a supplier.

Again — genuine complexity. But complexity that belongs in the inventory engine’s architecture, not in a custom development backlog. Each of these requirements is a configuration option in a platform designed for distribution. The system handles the complexity. The user experiences a streamlined workflow where the right unit of measure appears, the right lot is suggested, and the right location is directed automatically.

Fulfillment Complexity

Multi-source fulfillment across locations with different capabilities. Split shipment logic when no single location can fill an order completely. Backorder management with configurable rules for customer notification and substitution. Drop-ship orchestration where orders route to suppliers for direct fulfillment. Customer-specific compliance requirements — routing guides, packaging specifications, labeling formats — that vary by trading partner and carry financial penalties for non-compliance. Cross-dock workflows for products that should flow through the warehouse without being put away.

Complex operations. Straightforward system interaction. The fulfillment engine evaluates the variables, applies the rules, and directs the outcome. The warehouse associate picks what the system tells them to pick. The shipping station generates the compliant labels automatically. The customer gets what they ordered, packaged and documented correctly, without anyone in the chain needing to remember the compliance requirements from memory.

Financial Complexity

Multi-entity structures with inter-company transactions and transfer pricing. Revenue recognition rules that vary by transaction type. Landed cost calculations that include purchase price, freight, duty, brokerage, and handling — applied automatically at receipt and adjusted as actual costs replace estimates. Three-way matching between purchase orders, receipts, and vendor invoices with exception-based workflow for discrepancies. Sales tax and use tax calculation across jurisdictions. Multi-level financial reporting — by location, by entity, by region, by company — in real time.

Financially complex businesses need sophisticated financial engines. They don’t need 18-month implementations to get those engines running. On a unified data architecture where every financial event posts in real time from the originating transaction, much of this complexity resolves itself structurally. Landed costs apply at receipt because the receipt is a financial event. Inter-company entries post automatically because transfers trigger financial rules. Consolidation is instant because every entity’s data lives in the same database. The architecture handles the complexity so the month-end close doesn’t have to.

Integration Complexity

EDI with dozens of trading partners, each with their own document specifications and compliance requirements. E-commerce integration across multiple channels — your own web store, marketplace listings, B2B portals. Carrier integration with rate shopping, label generation, and tracking across multiple carriers. Payment processing. CRM synchronization. Specialized systems for route planning, demand forecasting, or category management. Each connection is a data flow that needs to be reliable, current, and maintainable.

Integration complexity is real, and it’s one of the areas where the wrong platform choice compounds cost for years. But the complexity should live in the integration framework — standardized APIs, event-driven webhooks, pre-built connectors maintained by the vendor — not in custom point-to-point integrations built by consultants and maintained by your team.

Where Complexity Should Live — and Where It Shouldn’t

The distinction that matters isn’t between simple businesses and complex businesses. It’s between complexity that lives in the platform’s architecture and complexity that’s pushed onto the implementation, the users, and the ongoing operation.

Complexity That Belongs in the Architecture

The heavy lifting — pricing calculations, inventory algorithms, allocation logic, financial posting rules, EDI translation, fulfillment routing optimization — should be handled by the platform’s internal engines. These engines should be deep, sophisticated, and capable of handling the most demanding distribution scenarios. The depth of the architecture is what makes the platform powerful.

This kind of complexity is invisible to users. The salesperson entering an order doesn’t see the pricing engine evaluating six overlapping pricing structures to arrive at the correct price. The warehouse associate picking a lot-controlled product doesn’t see the expiration management algorithm selecting the correct lot. The controller running a consolidated financial report doesn’t see the real-time aggregation engine assembling data from four entities and twelve locations. The complexity exists. It just doesn’t surface as difficulty.

Complexity That Shouldn’t Exist at All

A significant portion of what passes for “complexity” in enterprise ERP is artificial — created by the software’s architecture rather than by the business’s requirements.

The complexity of reconciling data between modules that maintain separate databases isn’t business complexity. It’s architectural deficiency. A unified data model eliminates it entirely.

The complexity of managing version-specific configurations across upgrade cycles isn’t business complexity. It’s a consequence of versioned deployment models. Continuous updates on a multi-tenant platform eliminate it entirely.

The complexity of coordinating between the vendor, the consulting firm, and your internal team isn’t business complexity. It’s organizational overhead created by the three-party implementation model. Vendor-direct implementation eliminates it entirely.

The complexity of maintaining custom code through platform updates isn’t business complexity. It’s technical debt created by inadequate configuration capabilities. Deep configuration on a multi-tenant platform eliminates it entirely.

When you strip away the artificial complexity — the complexity created by the platform’s limitations rather than by the business’s requirements — what remains is a set of genuine operational requirements that a well-architected platform handles through configuration and intelligent automation. The business is still complex. The system experience doesn’t have to be.

Complexity That Belongs With the User — Sparingly

Some complexity genuinely belongs in the user’s hands — decisions that require human judgment, exceptions that don’t fit algorithmic rules, situations where business context matters more than system logic.

A customer requesting special fulfillment handling that doesn’t fit any standard rule. A purchasing decision that factors in market intelligence the system doesn’t have. A pricing exception for a strategic customer relationship that justifies a margin sacrifice. A warehouse decision to override the system’s putaway suggestion because the associate knows something about the physical space that the system doesn’t.

These exceptions should be exactly that — exceptions. The system handles the routine. Humans handle the exceptional. If your team is spending most of their time making decisions that the system should be making automatically, the system isn’t handling its share of the complexity. Either the platform lacks the depth to automate those decisions, or it hasn’t been configured to do so.

The ratio between system-handled and human-handled decisions is one of the most revealing metrics for evaluating ERP effectiveness. On a well-implemented, purpose-built distribution platform, the vast majority of transactions — orders, allocations, picks, shipments, invoices — should flow through the system without manual intervention. The team’s attention should focus on the exceptions, the analysis, and the strategic decisions that actually benefit from human judgment.

Why Traditional Enterprise ERP Makes Complexity Worse

Here’s the paradox that the complexity myth obscures: traditional enterprise ERP systems, marketed as the solution for complex businesses, often make the operational experience more complex rather than less.

Complexity Through Fragmentation

Enterprise ERP suites assembled through acquisition are architecturally fragmented. The warehouse module was built by one company with one data model. The financial module was built by another with a different data model. The purchasing module, the order management module, the EDI module — each has its own lineage, its own architecture, and its own logic. They’re connected through middleware, integration layers, and batch processes that create the appearance of a unified system without the reality.

This fragmentation means that a single business process — receiving a shipment, for example — touches multiple architecturally distinct systems. The warehouse module handles the physical receipt. The inventory module handles the stock update. The purchasing module handles the PO matching. The financial module handles the accrual. Each transition between modules introduces latency, reconciliation overhead, and failure potential. The business process is simple. The system makes it complex.

Complexity Through Configuration Depth Without Configuration Design

Enterprise ERP platforms offer vast configuration options — thousands of settings, parameters, and switches that control system behavior. This sounds like flexibility. In practice, it’s a maze.

The configurations interact in ways that aren’t always documented or predictable. Setting A affects the behavior of Setting B, which changes the impact of Setting C. Consultants who’ve spent years working with the platform understand these interactions through experience. Everyone else — including your team — is navigating blind. A configuration change that solves one problem creates another. Testing every possible interaction is impractical, so configurations are validated against known scenarios and everyone hopes the unknown scenarios don’t produce unexpected behavior.

Deep configurability is valuable. Undesigned configurability — vast option spaces without clear guidance, interaction documentation, or guardrails — is a liability that masquerades as capability.

Complexity Through Consultant Dependency

When the system is too complex for your team to configure and too intricate for your operations leaders to understand without translation, every business change requires an intermediary. New workflow? Call the consultant. New report? Call the consultant. New integration? Call the consultant. Change in business rules? Consultant. The system isn’t complex because your business is complex. The system is complex because it was designed in a way that requires permanent professional services involvement, which generates permanent revenue for the implementation ecosystem.

The question a complex business should ask isn’t “which system is complex enough for us?” It’s “which system handles our complexity without imposing its own?”

How to Evaluate Whether a Platform Can Handle Your Complexity

Complex businesses need to test platforms against their actual operational reality, not against a standard demo. Here’s how.

Bring Your Hardest Scenarios

Identify the five scenarios that represent the peak complexity of your operation. The order with six different pricing structures overlapping on the same customer. The fulfillment scenario where three locations have partial stock and the customer needs everything by Thursday. The receiving situation with mixed lots, multiple POs, and a quantity discrepancy. The financial reporting requirement that spans three entities with inter-company eliminations.

Ask the vendor to demonstrate — live, in the system, not on a slide deck — how the platform handles each one. You’re not looking for perfection in a demo. You’re looking for whether the platform’s architecture can accommodate the scenario through configuration, or whether the answer is “we’d need to customize that” or “that would require a workaround.”

Test the Configuration Depth

Ask the vendor to change a business rule during the demo. Add a pricing tier. Modify an approval workflow. Create a new user-defined field. Adjust an allocation rule. Watch how it’s done. Is it a system setting that takes effect immediately? Or does it require a development request, a deployment cycle, or a consultant?

The speed and simplicity with which configurations can be changed tells you how the platform will feel after go-live, when your business inevitably evolves and the system needs to evolve with it.

Evaluate the Implementation Timeline Relative to Your Complexity

Ask the vendor how long implementation typically takes for a company with your specific complexity profile — your number of locations, your integration count, your pricing structure depth, your EDI trading partner count. A purpose-built platform with vendor-direct implementation should be able to cite a timeline that reflects your complexity without stretching into the multi-year range that enterprise implementations normalize.

If the timeline sounds like an enterprise engagement — 12 months, 18 months, 24 months — probe why. Is it because your business is genuinely that complex, or is it because the platform requires that much effort to configure? The distinction matters enormously. Business complexity is fixed. Platform complexity is a vendor choice.

Ask How Many Orders Process Without Manual Intervention

This is the metric that reveals whether a platform genuinely handles complexity or just stores data about it. In a well-configured distribution ERP, the percentage of orders that flow from entry through fulfillment, shipping, and invoicing without a human touch should be high — 80%, 90%, or more for standard transactions.

If the vendor can’t describe what that percentage looks like for companies similar to yours, or if the number is low, the platform isn’t automating complexity — it’s documenting it while your team does the actual work.

Talk to Reference Customers With Similar Complexity

Generic references are worthless for this evaluation. You need to talk to companies that share your specific complexity profile — similar product count, similar pricing structures, similar warehouse operations, similar integration landscape. Ask them: does the system handle your complexity, or do you work around it? What percentage of your daily transactions require manual intervention? How long did implementation take, and how much of that time was spent compensating for platform limitations versus configuring genuine business requirements?

The Architecture That Makes It Possible

Handling business complexity with operational simplicity isn’t magic. It’s architecture.

Unified data architecture eliminates the reconciliation complexity that fragmented systems create. When every transaction posts to a single data layer, there’s nothing to reconcile. The complexity of keeping modules in sync — which consumes enormous effort on legacy platforms — simply doesn’t exist.

Purpose-built domain logic means the pricing engine, the inventory engine, the allocation engine, and the fulfillment engine were designed for distribution’s specific complexity from the start. They’re not general-purpose engines stretched to fit. They handle distribution scenarios natively because that’s all they were built to do.

Multi-tenant architecture eliminates the complexity of version management, upgrade planning, and custom code maintenance. The platform evolves continuously. Your configurations persist through updates automatically. The entire category of complexity associated with keeping the system current disappears.

Configuration depth by design means the platform’s flexibility operates within a designed framework — not a sprawling maze of undocumented interactions, but a structured set of business rules, workflow parameters, and data extensions that are clear, testable, and maintained through platform updates.

Vendor-direct implementation eliminates the organizational complexity of coordinating between vendor, consultant, and internal teams. One organization. One point of accountability. One team that understands both the platform’s architecture and your business’s requirements deeply enough to configure the former around the latter.

How Bizowie Handles Complexity

Bizowie was built for complex distribution businesses that have been told they need painful software. They don’t.

Our pricing engine handles the full depth of distribution pricing — customer-specific, volume-tiered, contract-based, cost-plus, matrix, promotional — through configuration. Our inventory engine manages multi-location stock with real-time visibility, lot tracking, multiple units of measure, and expiration management as core architecture, not bolted-on modules. Our order management handles multi-source fulfillment, backorder logic, drop-ship orchestration, and customer-specific compliance natively. Our financial engine posts every transaction in real time to a unified ledger with multi-entity consolidation built in. And native EDI processes trading partner documents as standard workflow without middleware.

Advanced distribution capabilities — directed warehouse execution, pick optimization, cycle counting, cross-docking — are available as a dedicated module for operations that need that depth. Manufacturing is available for businesses that produce or assemble as well as distribute.

All of it runs on a continuously updated, multi-tenant platform. All of it is configured, not customized. All of it is implemented directly by the team that built it. And all of it is designed so that your team’s experience is straightforward even when the operations underneath are sophisticated.

Enterprise capability. Mid-market simplicity. Not because we’ve oversimplified the problem, but because we’ve put the complexity where it belongs — in the architecture — and kept it out of where it doesn’t — in your daily experience.

Test us against your complexity. Schedule a demo with Bizowie and bring the scenarios that make other vendors hesitate. The pricing structure nobody wants to demo. The fulfillment logic that requires three manual workarounds on your current system. The reporting requirement that takes your team a week to assemble. We built the platform for exactly these challenges — and we’ll show you how handling them doesn’t require handling the system.