Cloud ERP for Multi-Location Businesses: Managing Complexity Without Managing Servers

Adding a second warehouse is supposed to be a growth milestone. For distribution companies running the wrong ERP, it’s the beginning of an operational nightmare.

Suddenly, the system that worked well enough for one location can’t answer basic questions. How much total inventory do you have across both warehouses? Which location should fulfill this order? Can you promise delivery by Thursday if Warehouse A is out but Warehouse B has stock? If you transfer 500 units from one location to the other, what’s the financial impact — and does your system even know it happened?

On legacy ERP systems and small-business software, each location often feels like a separate planet. Inventory data lives in silos. Transfers require manual tracking. Financial consolidation is a month-end project that takes days. And every new location you add multiplies the complexity rather than scaling the operation.

Cloud ERP was supposed to fix this. Some platforms do. Many don’t — because multi-location capability that works in a demo and multi-location capability that runs a real distribution network are very different things. The difference comes down to data architecture, workflow design, and whether the platform was built for the operational reality of businesses that move physical product across multiple sites.

This guide explains what multi-location distribution actually demands from an ERP, where platforms fail, and what to look for when your business has outgrown the one-warehouse model.

Why Multi-Location Breaks Most ERP Systems

The core challenge of multi-location distribution isn’t technical complexity — it’s data coherence. Every function in the business needs to operate with full awareness of every location simultaneously, in real time, through a single system that presents the entire network as one unified operation.

That sentence is easy to write and extraordinarily difficult to deliver.

The Inventory Coherence Problem

In a single-location operation, inventory management is straightforward. Product is either here or it isn’t. The available quantity is a single number. Allocation means setting units aside for a specific order from one pool of stock.

In a multi-location operation, inventory becomes a matrix. The same SKU exists in multiple locations, in different quantities, with different statuses — available, allocated, in transit, on hold, in receiving, in quality review. Available-to-promise calculations must consider all locations, account for in-transit inventory, respect location-specific allocation rules, and produce an answer that’s current to the second.

ERP systems that weren’t designed for multi-location handle this by treating each location as a separate inventory pool — effectively running multiple independent inventory systems under one roof. A salesperson checking availability sees one location at a time. Allocation happens within a single location. Transfers between locations are processed as manual adjustments rather than tracked as systematic movements with full audit trails and financial impact.

The result is a business that technically has an ERP but practically runs its inventory on spreadsheets, phone calls between warehouse managers, and institutional knowledge about which location usually has what. The system can’t answer the most fundamental multi-location question — “do we have this product somewhere in our network, and can we get it to the customer on time?” — because it doesn’t see the network. It sees individual locations that happen to share a software license.

The Financial Consolidation Problem

Every location generates financial activity — purchases received, inventory valued, orders fulfilled, revenue recognized, expenses incurred. In a single-location business, financial reporting is straightforward. In a multi-location business, financial management requires real-time consolidation across every site, with the ability to report at the individual location level, the regional level, and the company-wide level simultaneously.

On systems with modular or location-segmented data architectures, financial consolidation is a periodic exercise. Each location’s data is collected, reconciled, and merged into a consolidated view — typically at month-end, sometimes more frequently but rarely in real time. Until that consolidation runs, the company-wide financial picture is an estimate based on partial data.

For distribution companies managing working capital carefully — where inventory represents the largest asset on the balance sheet and cash conversion cycles determine financial health — a financial picture that’s only accurate once a month is a financial picture that’s almost never accurate when decisions are being made.

The Fulfillment Routing Problem

When a customer orders a product and you have inventory in three locations, which one fulfills the order? The answer depends on factors that interact in complex ways: proximity to the customer, current inventory levels at each location, the cost of shipping from each location, whether the order can be consolidated into a single shipment or would require split fulfillment, customer preferences or requirements for ship-from location, and whether fulfilling from one location would create a stockout that affects other pending orders.

This is a decision that happens hundreds or thousands of times per day in a multi-location distribution operation. On systems that don’t support intelligent fulfillment routing, it’s made manually — by a person evaluating options, checking availability at each location, calculating shipping costs, and making a judgment call. At low volume, this works. At the volume most multi-location distributors operate, it’s a bottleneck that slows order processing, increases shipping costs, and produces suboptimal fulfillment decisions because no human can evaluate all the variables for every order in real time.

The Transfer Management Problem

Inventory transfers between locations are a daily reality in multi-location distribution. Rebalancing stock from an overstocked location to one approaching a stockout. Consolidating slow-moving inventory to reduce carrying costs at satellite locations. Positioning product ahead of seasonal demand shifts. Fulfilling inter-company transactions between divisions or entities that operate as separate legal structures.

Each transfer is simultaneously an inventory event, a logistics event, and a financial event. Product leaves one location’s inventory and enters another’s. Freight costs are incurred. In a multi-entity structure, transfer pricing and inter-company accounting entries may be required. The in-transit period — where the product has left Location A but hasn’t arrived at Location B — needs to be tracked as a distinct inventory state so that neither location’s available quantity is overstated.

Systems that handle transfers as simple inventory adjustments — subtract from one location, add to another — miss the operational and financial complexity entirely. The in-transit period isn’t tracked. The freight cost isn’t captured against the transfer. The inter-company accounting doesn’t happen automatically. And the inventory picture during the transit window is inaccurate at both locations.

What Multi-Location Distribution Actually Requires

The requirements aren’t exotic. They’re just numerous, interdependent, and unforgiving of shallow implementation. Here’s what the platform actually needs to do.

Unified Inventory Visibility Across All Locations — In Real Time

Every location’s inventory must be visible from every other location, updated in real time, and presented through a single view that shows network-wide availability without requiring the user to check locations one at a time.

This means a salesperson checking whether a product is available sees total network availability instantly — and can drill into which locations have stock, in what quantities, with what allocation status. It means purchasing decisions are informed by network-wide stock positions, not single-location snapshots. It means allocation decisions consider all eligible locations and apply rules — nearest warehouse, lowest shipping cost, inventory balance preferences — automatically rather than requiring manual evaluation.

Real-time unified visibility is only possible on a unified data architecture where all locations’ inventory data lives in a single, shared database. Systems that maintain separate inventory records per location and sync them periodically will always have a coherence gap — a window where one location’s data doesn’t reflect another location’s recent activity. In multi-location distribution, that gap is where mistakes happen: double-allocation of the same units, fulfillment promises based on inventory that’s already been picked at another site, purchasing decisions based on a network position that doesn’t reflect today’s transfers.

Intelligent Fulfillment Routing

The system should evaluate every order against the full set of fulfillment options and select the optimal source based on configurable rules. Not just “which location has the product” but “which location produces the best outcome across all relevant variables.”

Configuration should let you define what “best outcome” means for your business. For some distributors, it’s minimizing shipping cost. For others, it’s minimizing delivery time. For many, it’s a balance — ship from the nearest location that has sufficient stock, unless the cost differential exceeds a threshold, in which case evaluate alternatives. Some customers have ship-from requirements in their compliance specifications. Some orders should consolidate into a single shipment even if it means sourcing from a more distant location. Some products have handling requirements that restrict which locations can fulfill them.

The platform needs to evaluate these rules in real time, for every order, without manual intervention. When the routing logic handles the standard cases automatically, your team only intervenes on genuine exceptions — which is where their judgment adds value rather than being consumed by routine decisions the system should be making.

Transfer Management as a First-Class Workflow

Transfers between locations should be managed as complete workflows — requested, approved, picked, shipped, tracked in transit, received, and posted — with full visibility at every stage and automatic financial processing throughout.

The transfer workflow should generate appropriate documentation: a transfer order for the sending location, a receipt for the receiving location, and — in multi-entity structures — inter-company accounting entries that post automatically based on configured transfer pricing rules. During the transit window, inventory should be visible as “in transit” — not available at either location, but accounted for in the network-wide inventory position so that reporting remains accurate.

Suggested transfers should be system-generated based on configurable rules: when a location’s stock falls below its reorder point, the system should evaluate whether the needed inventory exists at another location before triggering a vendor purchase order. Network-wide inventory optimization — positioning stock where demand exists rather than where it was originally received — should be supported through systematic transfer recommendations rather than dependent on a planner’s memory and manual analysis.

Multi-Location Warehouse Execution

Each location has its own physical layout, its own storage characteristics, and potentially its own operational workflow. A distribution center with 100,000 square feet of racked storage operates differently from a 10,000-square-foot forward-stocking location with floor-stacked product.

The ERP needs to support location-specific warehouse configurations — bin structures, zones, pick paths, storage types, replenishment rules — while maintaining unified visibility and management across all locations. Warehouse execution at each site should be directed by the system through mobile devices, with real-time confirmation of every task, while management oversight spans all locations through consolidated dashboards and reporting.

For distribution companies with advanced warehouse operations at their primary facilities and simpler workflows at satellite locations, the platform should accommodate both levels of complexity without requiring the satellite locations to adopt processes designed for the distribution center or the distribution center to be constrained by the satellite’s simpler setup.

Location-Level and Consolidated Financial Reporting

Finance needs to see the business at every level of the organizational hierarchy simultaneously. Location-level P&L to evaluate individual site performance. Regional aggregation to compare geographic markets. Company-wide consolidation for executive reporting and external requirements. And the ability to move between these views fluidly, drilling from the consolidated picture down to the individual transaction at a specific location.

This requires financial data that posts in real time, that carries location identifiers from the originating transaction, and that aggregates without batch processing or manual consolidation. When a shipment confirms at Location B, the revenue recognition, the cost of goods sold, and the accounts receivable entry should post immediately — visible at the location level and at the consolidated level simultaneously, without waiting for a month-end close process to assemble the picture.

On a unified data architecture, this happens naturally because every financial transaction is tagged with its originating location and posted to a single financial database. On modular architectures with location-segmented data, consolidation requires periodic aggregation — and the real-time, multi-level financial visibility that multi-location management demands simply isn’t possible.

Consistent Business Rules With Location-Specific Flexibility

Most business rules should be consistent across the organization — pricing structures, credit policies, approval thresholds, accounting treatments. But multi-location operations inevitably require some location-specific variation. Different tax jurisdictions. Different shipping carriers available at different locations. Different cut-off times for same-day shipping based on location and carrier pickup schedules. Different warehouse workflows based on facility size and configuration.

The platform should support a hierarchy of business rules: organization-wide defaults that apply everywhere, with location-specific overrides where needed. This hierarchy should be manageable — a single administrative view where you can see which rules are universal and which are location-specific — rather than requiring separate configuration of every rule at every location.

Scalability That Makes Adding Locations Simple

Perhaps the most important requirement is the one that’s hardest to evaluate before you experience it: how easy is it to add the next location?

On legacy systems, adding a location is an IT project. New server capacity may be needed. The application requires configuration that may involve consultant assistance. Data structures need to be extended. Integrations need to account for the new site. The effort and cost of adding a location can rival a mini-implementation.

On a well-designed cloud ERP platform, adding a location should be a configuration exercise. Define the location. Set up the warehouse structure. Configure location-specific rules. Establish inventory. Begin operating. The infrastructure scales at the platform level — no capacity planning, no server provisioning, no architectural changes. The application was designed for multi-location from the start, so adding a site is extending a framework rather than bolting on an addition.

This scalability matters because multi-location distribution companies rarely stop at two or three locations. Acquisitions bring new facilities. Market expansion opens new regions. Customer requirements dictate forward-stocking positions. The ability to absorb new locations quickly and efficiently is a strategic capability that directly affects your ability to grow.

The On-Premise Multi-Location Nightmare

It’s worth dwelling on what multi-location management looks like on traditional on-premise ERP, because many companies evaluating cloud ERP are escaping this exact situation.

On-premise multi-location ERP has historically taken one of two approaches, both of which create problems.

The first approach runs a single instance of the ERP with multi-location awareness. This can work, but on-premise infrastructure means the system runs on servers at one physical location, and users at other locations access it over WAN connections — which introduces latency, bandwidth constraints, and a single point of infrastructure failure that affects every location.

The second approach runs separate ERP instances at each location, with periodic data synchronization between them. This eliminates the WAN dependency but creates an integration nightmare. Each location’s system becomes a data island. Consolidated reporting requires manual or batch aggregation. Inventory visibility across locations is always delayed. And maintaining consistent configurations across multiple independent instances is an ongoing administrative burden that grows with every location added.

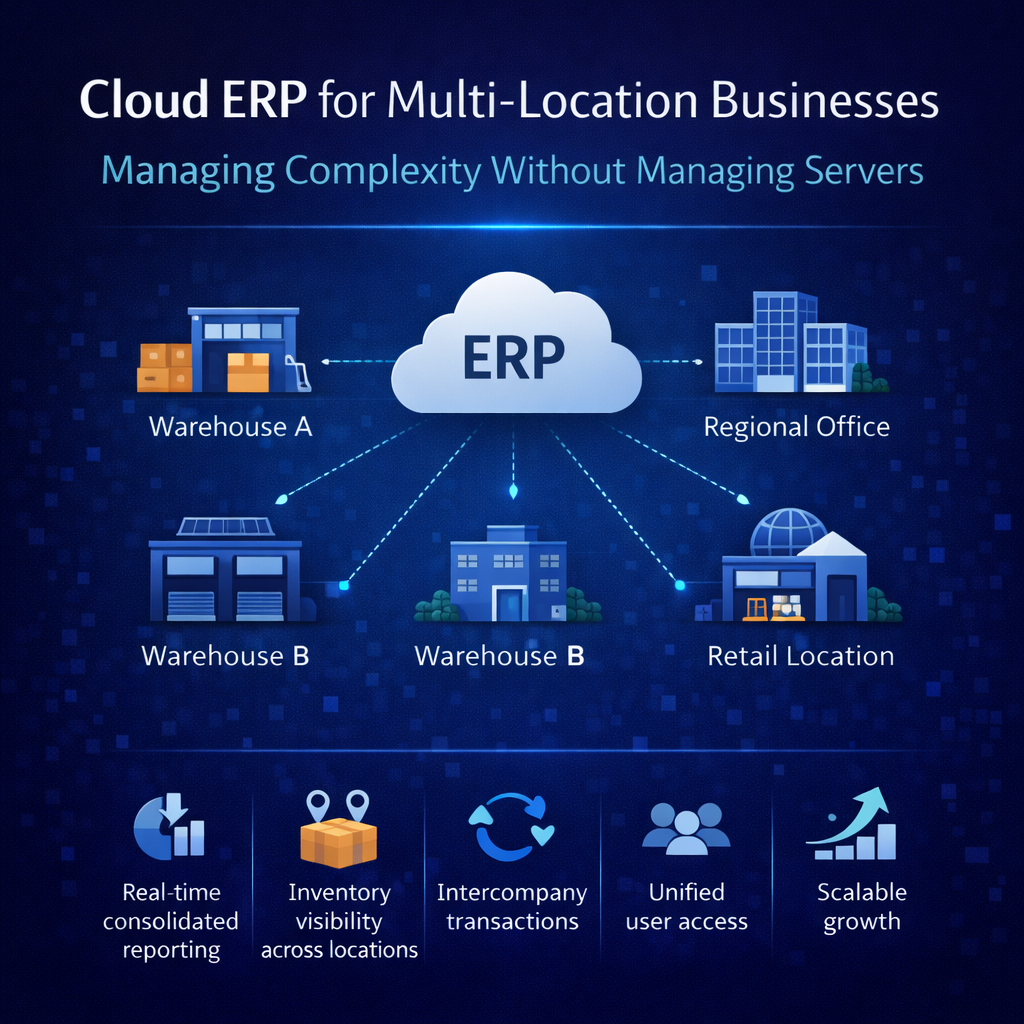

Cloud ERP eliminates both problems architecturally. The platform runs on cloud infrastructure accessible from any location with equal performance. Every location operates within the same application instance, reading from and writing to the same database. There’s no WAN dependency because every location accesses the platform through the internet with performance characteristics managed at the cloud infrastructure level. There’s no synchronization because there’s nothing to synchronize — all locations share the same real-time data.

This isn’t a marginal improvement over the on-premise multi-location experience. It’s a structural transformation that eliminates entire categories of complexity, cost, and compromise.

Evaluating Cloud ERP for Multi-Location Operations

When you’re evaluating platforms for a multi-location distribution business, the demo needs to go beyond showing a location dropdown on the inventory screen. Here’s how to test whether the platform genuinely supports the multi-location operation you’re running — or plan to run.

Ask the vendor to demonstrate a fulfillment scenario where the same product exists at three locations with different quantities, and show how the system selects the fulfillment source. Does it evaluate all locations automatically? Can you configure the routing rules? What happens when the optimal location can only partially fill the order — does the system handle split shipment, backorder, or transfer-and-fulfill?

Ask for a transfer workflow from request through receipt, including the in-transit period and the financial entries. If the vendor can show you every stage — with inventory accurately reflected during transit and financial entries posting automatically — the transfer capability is real. If they skip the in-transit visibility or the financial treatment, it’s shallow.

Ask how adding a new location works. Walk through the steps from creating the location to processing the first transaction. If it’s a configuration exercise that takes hours, the platform was designed for multi-location. If it involves infrastructure changes, consultant assistance, or extended setup projects, it wasn’t.

Ask about consolidated financial reporting across locations. Can the vendor show you a P&L by location, a P&L by region, and a consolidated company-wide P&L — all from current data, not from a month-end consolidation run? Can you drill from the consolidated number down to the individual transaction? The reporting capability reveals whether the data architecture supports real multi-location finance or just stores data by location and aggregates it later.

Ask what happens when two locations receive orders for the same product at the same moment and combined demand exceeds total network availability. Does the system manage allocation across locations in real time, or does each location allocate independently without awareness of the other? The answer reveals whether the platform sees a network or sees individual sites.

How Bizowie Handles Multi-Location Distribution

Bizowie was built on a unified data architecture where every location operates within the same real-time data layer. There are no location-specific databases to synchronize. No batch processes assembling a consolidated view. No coherence gaps between what one location sees and what another knows.

Inventory across every location is visible and current in real time — every receipt, every allocation, every pick, every transfer, every adjustment reflected instantly across the network. Available-to-promise calculations consider all locations simultaneously. Fulfillment routing applies configurable rules to select the optimal source for every order. Transfers are managed as complete workflows with in-transit tracking and automatic financial processing.

Financial reporting spans the full organizational hierarchy — location, region, company — in real time, with drill-down from the consolidated view to the individual transaction at any site. Adding a new location is a configuration task, not an infrastructure project. And because the platform runs on elastic cloud infrastructure, scaling from three locations to thirteen doesn’t require capacity planning, server provisioning, or architectural changes.

Advanced distribution capabilities — directed warehouse execution, pick optimization, lot and serial tracking, cycle counting — are available for locations that need that operational depth, while locations with simpler workflows operate on core inventory management within the same unified platform.

And every location, every workflow, and every financial view runs on the same continuously updated, multi-tenant platform — implemented directly by the team that built it.

See how a unified platform manages multi-location complexity. Schedule a demo with Bizowie and bring your multi-location scenarios — your trickiest fulfillment routing, your transfer workflows, your consolidated reporting requirements. We built the architecture for exactly this.